|

|

Deities in the Himalayan Tradition

Swami Jnaneshvara

In our tradition deities are

thought of only as symbols, not as realities to be worshipped. Swami

Rama explains it well in his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita

(3.11-3.12), where he writes:

The ignorant think that gods dwell in celestial worlds

and have power to control

human destiny. Such gods are merely projections of one's internal

organization;

the creation of gods in the external world is a projection of the

unconscious.

The belief in gods was created to help those who are not aware of their

internal

resources and are in need of an objectification of supernatural powers.

They need to believe in gods that will help them fulfill desires that they

feel

inadequate to fulfill through their own means. It is said that those who

have

seen gods are fools, for they have seen something of their own self and

mistakenly believe that they have seen gods. Externalists have created

gods for

their own convenience, but in actuality those gods are symbols of

unknown

phenomena that occur within.

For those aspirants who cannot contemplate on the attributeless Eternal,

symbols

are recommended by spiritual teachers. In the path of meditation certain

symbols

are used to make the mind one-pointed. The student is then advised to go beyond

the symbol to comprehend its meaning rather than remaining dependent on

the

symbol forever. Thus in meditation one leaves the symbol behind and goes

forward.

The ignorant worship the symbols without knowing and understanding that

which

lives behind and beyond the symbol. But if one is capable of exploring

that

which is being expressed by the symbol, he may eventually discover the

existence

of the formless archetype that is clothed in the forms of the symbol.

With

further work he may attain direct experience of the archetypes, not as

objects

but by becoming one with the archetypes themselves.

Swami Rama writes of meditation on the formless

Absolute in his commentary on Chapter 12 of the Bhagavad Gita (3.1-3.2):

Most people cannot fathom the idea of meditation

on the Absolute, which is formless and attributeless. Only a

fortunate few are able to attain that highest state of realization.

The path of bhakti (devotion) is considered to be superior for those

who are unable to realize the pure Self. It is difficult to conceive

of meditating without a form or object on which to focus the

mind.... Whether one follows the path of bhakti or the path of jnana

(Self-realization), a one-pointed mind is important, and that cannot

be achieved without concentration. Concentration of mind and faith

are essentials for treading either path. The ordinary sadhaka or

aspirant should have a concrete form for concentration and

meditation before his mind is prepared for the higher realms.

Swami Rama describes the meaning of the symbol of

Ganapati as follows in his commentary on Chapter 3 of the Bhagavad Gita

(3.21-3.24):

In the ancient times there were no printing

presses, tape recorders, or writing paper. Therefore the ancients

left certain symbols for future generations so that they could

understand the way the ancients lived. For example, if the pictorial

symbol of Ganapati, the elephant god, is properly understood and

analyzed, it becomes clear that the ancients described the ideal

qualities of a leader through that symbol. The head of an elephant

symbolizes that a great leader should not be violent, for elephants

are very calm. They do not live on the flesh of other beings;

elephants are vegetarians, and they are both healthy and

intelligent. Using an elephant as an example dispels the notion that

it is necessary to eat meat in order to maintain health and vigor.

Ganapati has a big belly, which means the leaders should be able to

accept all sorts of suggestions from various quarters for the sake

of doing justice and selfless service to society. Ganapati is shown

with a mouse, meaning that leaders should have counselors like mice

who, with the help of their sharp teeth, can cut the net of

entanglements and conspiracy that tend to develop around leaders.

There are many other aspects, such as the cross, the star of David,

and the lotus that are adored and worshipped without knowing their

meanings. That is a serious error. The method of understanding such

symbolism is a knowledge in itself, like the method of studying

dream symbols. It should be studied if one is to understand the

world within and without.

Examples of Symbols

Following are a few examples of how this works, where

some may consider these as deities or gods to be followed, petitioned,

or worshipped, but which are actually symbols. The symbols mentioned and

the descriptions are not meant to be complete, but rather, are just to

give you an introduction to this process.

Hanuman: The monkey is held as a symbol of the

human mind, and its habit of running here and there, constantly active

and never restful; it is fickle like the monkey. Hanuman is a symbol of

training that monkey mind, bringing it to peace and tranquility. Prayer

to Hanuman as a deity is thought to bring devotion and purity.

Ganesha: While there are many other

symbolisms, Ganesha is a reminder to be like the elephant, strong and

wise. The elephant is independent, a strong creature living in the wilds

of the jungle, harming no one for food, as he is vegetarian. Others view

Ganesha as having human form, but with an elephant head; he is

petitioned as a remover of obstacles.

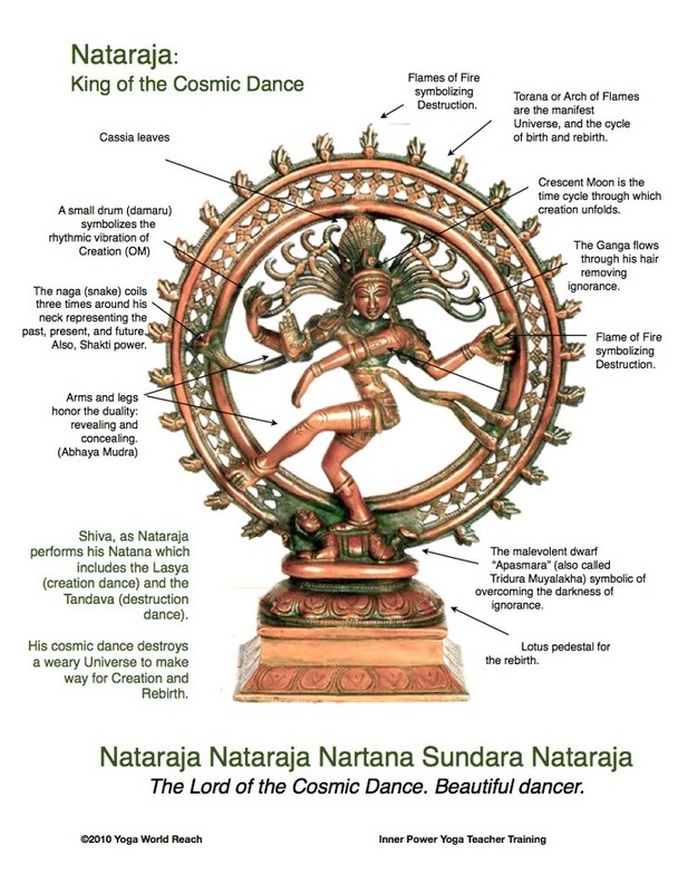

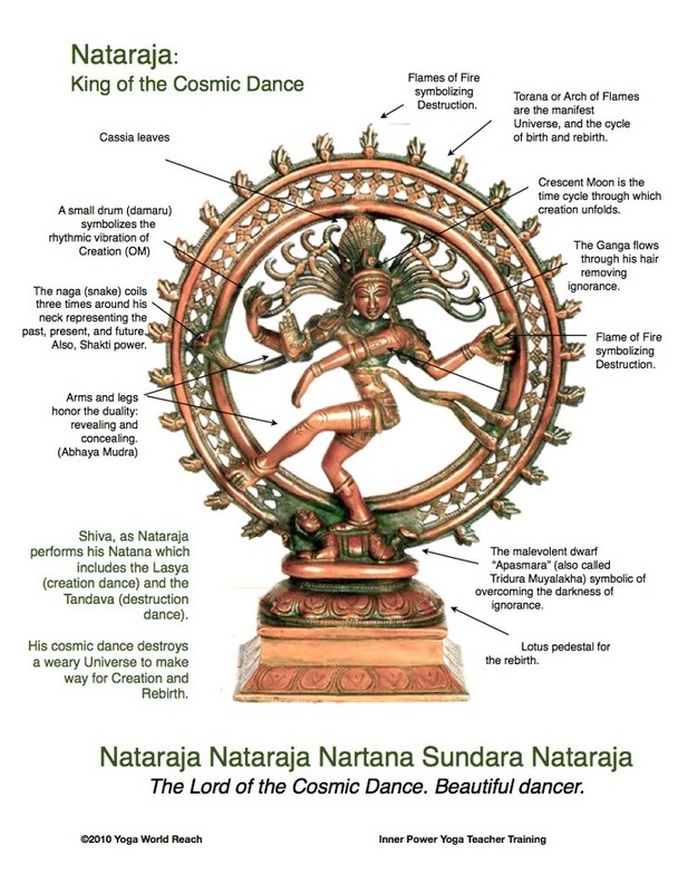

Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh (Shiva, Rudra): As

symbols, these represent the three universal processes of coming into

being, existing for some time, and going (receding back into the

formless). A flower comes, is, and goes. Our lives in these physical

bodies in this world goes through this process of birth, living, and

dying. Thoughts also come, stay for a while, and naturally dissipate.

Others view these symbols as deities to be worshipped or petitioned.

Shiva and Shakti: These are universal process

of the static ground (shiva) and the active (shakti) manifesting outward

through many levels. As a metaphor, it is somewhat like the countless

words and sentences which may be written with the use of the underlying

same ink. While the ground is shiva (which is one and the same with

shakti), it is the power of shakti that manifests as the entire universe

and all its diversity. Others perform rituals as if Shiva and Shakti are

anthropomorphic beings to be solicited for various reasons.

Mahatripurasundari: Central to the practices

in our tradition is meditation and contemplation on the one

consciousness which is the source of, and permeates the three (tri)

levels (cities or "pura") of sleep, dreaming, and waking. That

consciousness is considered to be great ("maha") and most beautiful ("sundari").

Others worship her as a goddess.

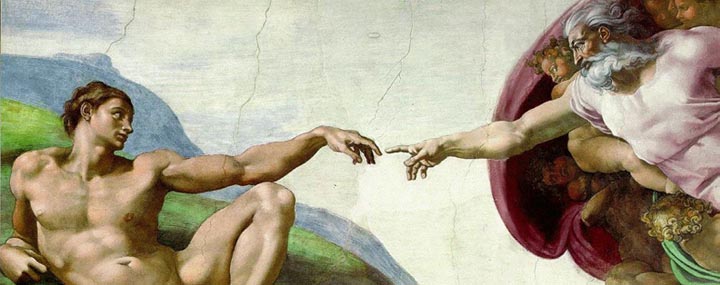

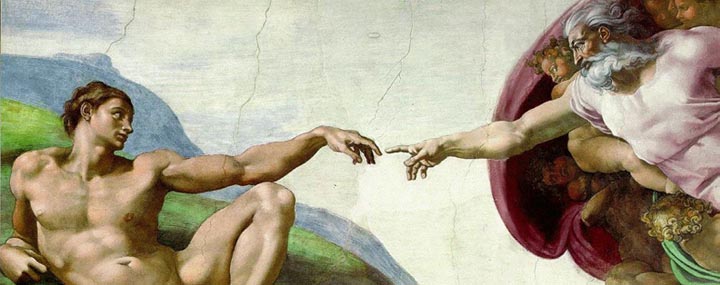

There is no gray bearded god in the sky who is the creator and manager

of the physical universe. Rather, to a yogi of our tradition, this

beautiful art from the Sistine Chapel would be seen as a symbol of the

one Reality manifesting outward as life in our world, as humanity and

other beings, the expression of sat, cit, ananda (existence,

consciousness, and bliss).

Stories and Symbols

It seems to be a common human practice to wrap principles of living

inside of stories, whether through poetry, books, or screenplays. The

ancient symbols of deities were described in stories, such as Krishna in

the Bhagavad Gita, which is part of the epic poem, Mahabharata. We can

wonder if, over the coming centuries and millenia, todays stories of

heroes may also come to be perceived as deities, and treated as

religious symbols to be worshipped. We each have the choice of how to

view these characters and their stories: are they "real" or are they

symbols used to convey wisdom? Reflecting on such questions can give us

greater insight about how the ancient symbols have come to been seen as

something other than the symbols they actually are.

-------

This site is devoted to

presenting the ancient Self-Realization path of

the Tradition of the Himalayan masters

in simple, understandable and beneficial ways, while not compromising

quality or depth. The goal of our sadhana or practices is the highest

Joy that comes from the Realization in direct experience of the

center of consciousness, the Self, the Atman or Purusha, which is

one and the same with the Absolute Reality.

This Self-Realization comes through Yoga meditation of the Yoga

Sutras, the contemplative insight of Advaita Vedanta, and the

intense devotion of Samaya Sri Vidya Tantra, the three of which

complement one another like fingers on a hand.

We employ the classical approaches of Raja, Jnana, Karma, and Bhakti

Yoga, as well as Hatha, Kriya, Kundalini, Laya, Mantra, Nada, Siddha,

and Tantra Yoga. Meditation, contemplation, mantra and prayer

finally converge into a unified force directed towards the final

stage, piercing the pearl of wisdom called bindu, leading to the

Absolute.

|

|