|

|

Yoga

Sutras 2.1-2.9:

Minimizing

Gross Colorings

that Veil the Self

(Previous

Next Main)

Reduce colorings by Kriya Yoga: In these first few

sutras of Chapter 2, specific methods are

being introduced on how to minimize the gross colorings (kleshas)

of the mental obstacles, which veil the true Self. (The later sutras of

this chapter deal with the the subtle colorings of mental

obstacles). Reduce colorings by Kriya Yoga: In these first few

sutras of Chapter 2, specific methods are

being introduced on how to minimize the gross colorings (kleshas)

of the mental obstacles, which veil the true Self. (The later sutras of

this chapter deal with the the subtle colorings of mental

obstacles).

Living the three practices of Kriya Yoga: The first part of the

process of minimizing the gross coloring is called Kriya Yoga, and leads

one in the direction of samadhi. Kriya Yoga involves three parts (2.1-2.2):

- Training the senses (See article on Ten

Senses)

- Studying yourself in the context of

teachings

- Surrender of klishta (colored) thought

impressions

(Uses of the word Kriya: It is important to note that the name Kriya

Yoga is used in a variety of ways. This is described below

in the description of sutra 2.1)

Reducing the colorings: The five kinds of

coloring (2.3) are related to spiritual

ignorance (2.5), I-ness (2.6),

attraction (2.7), aversion (2.8),

and fear (2.9). The process of dealing with these

coloring moves through four stages of active, separated, attenuated, and

seed (2.4). (The process of coloring was first

introduced in sutra 1.5)

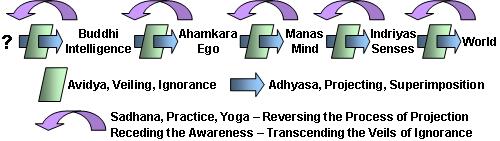

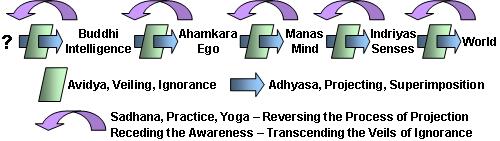

Transcending four kinds of ignorance: Ignorance

(avidya) is the root coloring that leads to the others. It evolves and

dissolves in stages (2.4),

and is of four types (2.5), including: 1) mistaking the temporary for the

eternal, 2) impure for pure, 3) pain for pleasure, and 4) not-self for self.

Foundation: Chapter

1 included the definition of Yoga (1.1-1.4),

the principle of uncoloring thought patterns (1.5),

practice and non-attachment (1.12-1.16),

as well as a framework for focusing (1.17-1.18),

stabilizing, and purifying the mind (1.19-1.22,

1.30-1.32, 1.33-1.39).

With this foundation, one can now begin the process of reducing the

colorings of the thought patterns.

See also these articles: Each

of these articles will add a complementary perspective on viewing and

dealing with the coloring of the deep impressions of the mind:

Klishta and Aklishta Thoughts

Witnessing Your Thoughts

Karma and the sources of Actions, Speech, and

Thoughts

Regulating Lifestyle and the Four Basic Urges

Training the Ten Senses or Indriyas

Four Functions of Mind

4 Levels and 3 Domains of Consciousness

The 5 Koshas or Sheaths

top

2.1

Yoga in the form of action (kriya yoga) has three parts: 1) training and

purifying the senses (tapas), 2) self-study in the context of teachings (svadhyaya),

and 3) devotion and letting go into the creative source from which we

emerged (ishvara pranidhana).

(tapah svadhyaya ishvara-pranidhana kriya-yogah)

- tapah = accepting the

purifying aspects of painful experience, purifying action, training

the senses

- svadhyaya = self-study

in the context of teachings, remembrance of sacred word or mantra

- ishvara = creative

source, causal field, God, supreme Guru or teacher

- pranidhana = practicing

the presence, dedication, devotion, surrender of fruits of practice

- kriya-yogah = yoga of

practice, action, practical yoga

These three practices work together:

A bit of reflection will show clearly how the three principles (tapas,

svadhyaya, ishvara pranidhana) work

together. The principles are really familiar to us all, but seeing them

clustered together as a single mode of spiritual practice is very useful. The

mind can easily remember the three principles together as a single practice; it

becomes a companion in daily life.

Reminding yourself of Kriya Yoga:

When thinking about life and spiritual practices, it is easy then to

remind yourself of this foundation by internally saying such words as,

"I need to train my senses, explore within, and let go of these

attachments and aversions." Contained in a simple sentence like this

is the outline of Kriya Yoga (that simple sentence contains tapas,

svadhyaya, and ishvara pranidhana). Then, the many other practices of the Yoga

Sutras, along with other practices you might do, can be done in this

straightforward context. Remember that this is the gross level of

weakening the colored thought patterns, and that this is preparation for

the subtler part, which is done in meditation (2.10-2.11).

Ishvara pranidhana: The emphasis

of ishvara pranidhana practice is the release or surrender that is done in

a sincere, dedicated, or devotional attitude. It is easy to get caught up

in debates over the nature of God, Guru, creative source, and teacher.

Yoga is very broad and non-sectarian, leaving it open to each individual

how to perceive these realities. The more important part is that of

letting go rather than holding on to the images and desires of the senses

(tapas) and the personal characteristics and makeup uncovered through

introspection (svadhyaya). Without such a letting go, the other two of the

three practices in this sutra would be of little or no value; you would

have knowledge but little freedom.

Meaning of Ishvara: In the Upanishads,

the word Īśvara is used to denote a state of collective consciousness. Thus, God

is not a being that sits on a high pedestal beyond the sun, moon, and stars; God

is actually the state of Ultimate Reality. But due to the lack of direct

experience, God has been personified and given various names and forms by

religions throughout the ages. When one expands one's individual consciousness

to the Universal Consciousness, it is called Self-realization, for the

individual self has realized the unity of diversity, the very underlying

principle, or Universal Self, beneath all forms and names. The great sages of

the Upanishads avoid the confusions related to conceptions of God and encourage

students to be honest and sincere in their quests for Self-realization.

Upanishadic philosophy provides various methods for unfolding higher levels of

truth and helps students to be able to unravel the mysteries of the individual

and the universe. (from Swami Rama in the section What God Is from Enlightenment

Without God)

Modern versions of Kriya Yoga:

Some modern teachers and institutions consider the entire Yoga Sutras to

be Kriya Yoga, although Patanjali

only relates the term Kriya Yoga to these three foundation practices.

Often, breathing practices with attention

along the spine (sushumna) are included, along with other physical practices. It

is useful for the student of Yoga to be aware of these different

approaches,

so as to not get confused by the various public offerings. These adjunct

practices themselves are very useful, whether or not you consider them to

be a part of Kriya Yoga, or separate practices coming from Pranayama

(breath practice, 2.49-2.53), Hatha

Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, or Tantra Yoga, for example. In addition, the word Kriya

literally means actions, and one might ask a teacher or ashram, "What

is your Kriya?" meaning to inquire, "What kind of

practices do you do and teach here?" Thus, many practices might be

included in the phrase Kriya Yoga. To the Himalayan

Masters, Kriya Yoga is a part of the whole of Yoga.

top

2.2

That Yoga of action (kriya yoga) is practiced to bring about samadhi and

to minimize the colored thought patterns (kleshas).

(samadhi bhavana arthah klesha tanu karanarthah cha)

- samadhi = deep

absorption of meditation, the state of perfected concentration

- bhavana = to bring

about, cultivate

- arthah = for the purpose

of

- klesha = colored,

painful, afflicted, impure

- tanu-karana = minimize,

to make fine, attenuate, weaken

- arthah = for the purpose

- cha = and

Reasons for Kriya Yoga: This sutra

provides the context and reason for doing the Kriya Yoga (tapas, svadhyaya,

ishvara pranidhana):

- Kriya Yoga purifies the mind, allowing

the gross level of the colorings (2.3) to be

weakened (2.4).

- Kriya Yoga is an early stage of the

journey, which leads directly towards samadhi.

Seeing the systematic process: It

is most useful to see the systematic nature of these practices, whereby

you first do the gross level of stabilizing the mind, such as through the

methods in Chapter 1 (1.30-1.32, 1.33-1.39).

Then, the gross colorings (kleshas) are attenuated through Kriya Yoga,

which is the subject of the sutras discussed in this section (tanu-karana

means attenuating the kleshas or colorings, afflictions, or impurities). Then,

building upon that foundation, the subtler attenuation is done (2.10-2.11),

and the breaking of the alliance with karma (2.12-2.25).

There is a very important principle in this

sutra. That is, the means of reducing the kleshas is suggested. We

might encounter many explanations, definitions, discussions, or debates

about the meaning of the word klesha, but it is clear from the next sutra (2.3)

that they have something to do with mental habits like attractions

and aversions, with which we are all familiar. It can be argued that the

meaning of klesha is extremely subtle, however, it also has very

practical application to even the beginning level of meditator. Again, every

one of us knows the problems caused by our attractions and aversions.

Here, this sutra is telling us that the

means of weakening (though not yet eliminating) those negative habits of

mind is the three-fold method in the last sutra (2.1).

While students of meditation might struggle with all of the seemingly

complex principles, here is a simple suggestion that has only three parts.

That is very, very useful in that these three principles of tapas, svadhyaya,

and ishvara pranidhana are relatively easy to understand at some level, and

are highly effective in weakening the mental clutter.

top

2.3

There are five kinds of coloring (kleshas): 1) forgetting, or ignorance

about the true nature of things (avidya), 2) I-ness, individuality, or

egoism (asmita), 3) attachment or addiction to mental impressions or

objects (raga), 4) aversion to thought patterns or objects (dvesha), and

5) love of these as being life itself, as well as fear of their loss as

being death.

(avidya asmita raga dvesha abhinivesha pancha klesha)

- avidya = spiritual

forgetting, ignorance, veiling, nescience

- asmita = associated with

I-ness

- raga = attraction or

drawing to, addiction

- dvesha = aversion or

pushing away, hatred

- abhinivesha = resistance

to loss, fear of death of identity, desire for continuity, clinging to

the life of

- pancha = five

- klesha = colored,

painful, afflicted, impure; the root klish means to cause

trouble; (klesha is the noun form of the adjective klishta)

See also the Five

Kleshas section of Witnessing Your Thoughts A

most important practice in Yoga: Cultivating self-awareness of the

five kleshas is one of the most important foundation practices in the

entire science of Yoga. Note that in Chapter 1 of the Yoga Sutra, the

first four sutras describe or define Yoga, and that the very next sutra (1.5)

introduces the concept of the many levels of thought patterns being either

klishta (colored) or aklishta (uncolored). Now, in this current sutra (and

Kriya Yoga in general), the concept is expanded, describing the nature of

the five individual kleshas. In Kriya Yoga, the gross level of coloring is

dealt with (2.1), while the next few sutras begin the

process of dealing with the subtler colorings (2.10-2.11,

2.12-2.25).

It works in stages, first reducing the gross,

and then the subtle. To be aware of the practice of self-awareness or

witnessing of the kleshas of our own mind is a very useful thing to do.

The five kleshas: Each of the five

kleshas are described separately in the forthcoming sutras:

- Avidya (2.4,

2.5) = spiritual

forgetting, ignorance, veiling, nescience

- Asmita (2.6)

= associated with

I-ness

- Raga (2.7)

= attraction or

drawing to, addiction

- Dvesha (2.8)

= aversion or

pushing away, hatred

- Abhinivesha (2.9)

= resistance

to loss, fear of death of identity, desire for continuity, clinging to

the life of

Four stages of kleshas: The five

colorings (klishta) of individual deep thought patterns are in one of four

states. These are described in the next sutra (2.4), as

part of introducing specifics about the nature of the five kleshas

themselves.

Allow streams of individual thoughts

to flow: One of the best ways to get a good understanding of

witnessing the kleshas (colorings) is to sit quietly and

intentionally allow streams of individual thoughts to arise. This doesn't

mean thinking or worrying. It literally is an experiment in which you

intentionally let an image come. It is easiest to do with what seem to be

insignificant impressions.

For example, imagine a fruit, and notice

what comes to mind. An apple may come to mind, and you simply note

"Attraction" if you like it, or are drawn to it. It may not be a

strong coloring, but maybe you notice there is some coloring. You may

think of a pear, and note that there is an ever so slight

"aversion" because you do not like pears.

Experiment with colorings: Allow

lots of such to images come. One of the things I have done often with

people is to grab about 10-15 small stones in my hand, and ask a person to

pick one they like. Then I ask them to pick one they are less drawn to

(few people will say they "dislike" one of the stones). It is a

very simple experiment that demonstrates the way in which attractions and

aversions are born. It is easier at first to experiment with witnessing

thoughts for which there is only slight coloring, only a small amount of

attraction or aversion.

You can easily run such experiments with

many objects arising into the field of mind from the unconscious. You can

also easily do this by observing the world around you. Notice the

countless ways in which your attention is drawn to this or that object or

person, but gently or strongly turns away from other objects or people.

Though it is a bit harder to do, notice

the countless objects you pass by everyday for which there is no response

whatsoever. These are examples of neutral impressions in the mind field.

Gradually witness stronger colorings:

By observing in this way, it is easier to gradually witness stronger

attractions and aversions in a similar way. When we can begin the process

of witnessing the type of coloring, then we can start the process of

attenuating the coloring, which is discussed in the next section.

top

2.4

The root forgetting or ignorance of the nature of things (avidya) is the

breeding ground for the other of the five colorings (kleshas), and each of

these is in one of four states: 1) dormant or inactive, 2) attenuated or

weakened, 3) interrupted or separated from temporarily, or 4) active and

producing thoughts or actions to varying degrees.

(avidya kshetram uttaresham prasupta tanu vicchinna udaranam)

- avidya = spiritual

forgetting, ignorance, veiling, nescience

- kshetram = field,

breeding ground

- uttaresham = for the

others

- prasupta = dormant,

latent, seed

- tanu = attenuated,

weakened

- vicchinna = distanced,

separated, cut off, intercepted, alternated

- udaranam = fully active,

aroused, sustained

Systematically reduce the colorings:

These colorings (kleshas) are either: 1) active, 2) cut off, 3)

attenuated, or 4) dormant. We want to be able to observe and witness these

stages so that we can systematically reduce the coloring. Then the thought

patterns are no longer obstacles to deep meditation, and that is the goal.

(See the articles on Klisha and Aklishta Vrittis

and Karma and the sources of Actions, Speech, and

Thoughts)

Four stages of coloring: The

starting point is to observe what is the current state of the coloring

of individual thought patterns. This self-awareness practice becomes a

gentle companion in daily life and during meditation:

1. Active,

aroused (udaram): Is the thought pattern active on the surface of

the mind, or playing itself out through physical actions (through the

instruments of action, called karmendriyas,

which include motion, grasping, and speaking)? These thought patterns and

actions may be mild, extreme, or somewhere in between. However, in any

case, they are active.

2.

Distanced, separated, cut off (vicchinna): Is the thought pattern

less active right now, due to there being some distance or separation. We

experience this often when the object of our desire is not physically in

our presence. The attraction or aversion, for example, is

still there, but not in as active a form as if the object were right in

front of us. It is as if we forgot about the object for the now. It is

actually still colored, but just not active (but also not

really attenuated).

3.

Attenuated, weakened (tanu): Has the thought pattern not just

been interrupted, but actually been weakened or attenuated?

Sometimes we can think that a deep habit pattern has been attenuated,

but it really has not been weakened. When we are not in the

presence of the object of attachment or aversion, that

separation can appear to be attenuation, when it actually is

just not seen in the moment.

This is one of

the big traps of changing the habits or conditionings of the mind. First,

it is true that we need to get some separation from the active

stage to the distanced stage, but then it is essential to start to attenuate

the power of the coloring of the thought pattern.

4. Dormant,

latent, seed (prasupta): Is the thought pattern in a dormant or

latent form, as if it were a seed that is not growing at the

moment, but which could grow in the right circumstances?

The thought

pattern might be temporarily in a dormant state, such as when asleep, or

when the mind is distracted elsewhere. However, when some other thought

process comes, or some visual or auditory image comes in through the eyes

and ears, the thought pattern is awakened again, with all of its coloring.

Eventually the

seed of the colored thought can be burned in the fire of meditation, and

a burnt seed can no longer grow.

Where does all of this go?

Through the process of Yoga meditation,

the thought patterns are gradually weakened, then can mostly remain in a

dormant state. Then, in deep meditation the "seed" of the

dormant can eventually be burned, and a burned seed can no longer grow.

Then, one is free from that previously colored thought pattern.

Example:

An example will help to understand the way these four stages work

together. We'll use the physical example of four people, in relation to

smoking cigarettes, because the example can be so clear. The principles

apply not only to objects such as cigarettes, but also to people,

opinions, concepts, beliefs, thoughts or emotions. The principle also

applies not only to gross level thoughts, but the subtlest of mental

impressions.

- Person A:

Has never smoked and has never felt any desire to smoke. When Person A

sees a cigarette, he recognizes what it is. There is a memory

impression in the chitta, but it is completely neutral--it just is a

matter or recognition. It is not colored; it is aklishta.

(The thought of cigarettes might be colored by aversion, if he is

offended by smoking, but that is a different example.)

- Person B:

Has smoked for many years, but then quit several years ago.

Occasionally she still says, "I'd kill for a cigarette!" but

does not smoke due to health reasons. Her deep impression of

cigarettes remains colored, and is actively playing out in both

the unconscious and conscious, waking states. At times, the impression

of cigarettes might not be active, such as when she is asleep, or

doing some other distracting activity. However, at the latent level,

the impression is still very colored in a potential form.

- Person C:

Has smoked for many years, but then quit several years ago. He always

says, "Oh, no, I don't want a cigarette; I never even think about

it." At the same time his gestures and body language reveal

something different. He may have very colored mental

impressions of attachment, but they are not allowed to surface

into consciousness. There is separation from the thought pattern, but

the coloring has not truly been attenuated (even though

it goes into latent form during sleep, or when the mind is

distracted). This kind of blocking the coloring is not what is

intended in Yoga science.

- Person D:

Smoked for many years, but then quit several years ago. After some

time of struggling with the separation or cutting off phase (Vicchinna),

she then sat with this desire during meditation, allowed the awareness

of the attachment to rise, gently refrained from engaging the

impressions, and watched the coloring gradually fade. During that

time, the thought patterns were sometimes active, sometimes separated,

and sometimes temporarily dormant. However, it is now as if she were a

non-smoker. The desire has returned to seed form or is completely

gone, not only when asleep, or when the mind is distracted, but also

when in the presence of cigarettes in the external world.

Notice the stage of individual

thoughts: We want to observe our thinking process often, in a

gentle, non-judging way, noticing the stage of the coloring of thought

patterns. It can be great fun, not just hard work. The mind is quite

amusing the way that it so easily and quickly goes here and there, both

internally and through the senses, seeking

out and reacting to the objects of desire. (See also the article on the four

functions of mind)

There are many thoughts traveling in the

train of mind, and many are colored. This is how the mind works; it

is not good or bad. By noticing the colored thought

patterns, understanding their nature by labeling them, we can increasingly

become a witness to the whole process, and in turn, become free

from the coloring. Then, the spiritual insights can more easily

come to the forefront of awareness in life and meditation.

Train the mind about coloring: An

extremely important part of attenuating, or reducing the coloring

of the colored thought pattern is to train the mind that this coloring

is going to bring nothing but further trouble (This is described in Sutra 2.33).

It means training the mind that,

"This is not useful!". This simple training is the beginning of attenuating

the coloring (The process starts with observing, but then moves on to

attenuating). It is similar to training a small child; it all begins by

labeling and saying what is useful and not useful. Note that

this is not a moral judgment as to what is good or bad. It is more like

saying whether it is more useful to go left or right when taking a

journey.

Often, we are stuck in a cycle:

Often in life, we find that the colored thought patterns move

between active and separated stages, and then back to active. They go in a

cycle between these two. Either they are actively causing challenges, or

we are able to get some distance from them, like taking a vacation.

Break the cycle: However, it is

possible that we may never really attenuate them when engaged in

such a cycle, let alone get the colorings down into seed form, when

we are stuck in this cycle. It is important to be aware of this

possibility, so that we can intentionally pursue the process of weakening

the strength of the coloring.

Meditation attenuates coloring:

This is where meditation can be of tremendous value in getting free from

these deep impressions (2.11). We

sit quietly, focusing the mind, yet intentionally allow the cycling

process to play out, right in front of our awareness. Gradually it

weakens, so we can experience the deeper silence, where we can come in

greater touch with the spiritual aspects of meditation.

top

2.5

Ignorance (avidya) is of four types: 1) regarding that which is transient

as eternal, 2) mistaking the impure for pure, 3) thinking that which

brings misery to bring happiness, and 4) taking that which is not-self to

be self.

(antiya ashuchi duhkha anatmasu nitya shuchi sukha atman khyatih avidya)

- antiya = non-eternal,

impermanent, ephemeral

- ashuchi = impure

- duhkha = misery, painful,

sorrowful, suffering

- anatmasu = non-self,

non-atman

- nitya = eternal,

everlasting

- shuchi = pure

- sukha = happiness, pleasurable,

pleasant

- atman = Self, soul

- khyatih = taking to be,

supposing to be, seeing as if

- avidya = spiritual

forgetting, ignorance, veiling, nescience

Vidya

is with knowledge: Vidya

means knowledge, specifically the

knowledge of Truth. It is not a mere mental knowledge, but the spiritual

realization that is beyond the mind. When

the "A" is put in front of Vidya (to make it Avidya),

the "A" means without.

Avidya is without knowledge:

Thus, Avidya means without Truth or without

knowledge. It is the first form of forgetting the spiritual Reality. It is

not just a thought pattern in the conventional sense of a thought pattern.

Rather, it is the very ground of losing touch with the Reality of being

one with the ocean of Oneness, of pure Consciousness.

Meaning of ignorance: Avidya

is usually translated as ignorance,

which is a good word, so long as we keep in mind the subtlety of the

meaning. It is not a matter of gaining more knowledge, like going to

school, and having this add up to receiving a degree. Rather, ignorance is

something that is removed, like removing the

clouds that obstruct the view.

Then, with the ignorance (or clouds) removed, we see knowledge or Vidya

clearly.

Even in English, this principle is in the

word ignorance. Notice that the word contains the root of ignore,

which is an ability that is not necessarily negative. The ability to ignore

allows the ability to focus. Imagine that you are in a busy restaurant,

and are having a conversation with your friend. To listen to your friend

means both focusing on listening, while also ignoring the other

conversations going on around you. However, in the path of

Self-realization, we want to see past the veil of ignorance, to no

longer ignore, and to see clearly.

|

Avidya is

confusion of one for the other

|

|

Temporary

Impure

Painful

Not-self

|

<----->

<----->

<----->

<----->

|

Eternal

Pure

Pleasureful

Self |

Avidya is the ground for the other

colorings: Avidya

is like a fabric, like a screen on which a

movie might then be projected. It is the ground in which comes the other

four of the colorings described below. Avidya

(ignorance) is somewhat like making a mistake, in which one thing is

confused for another. Four major forms of this are:

- Seeing the temporary as

eternal: For example,

thinking that the earth and moon are permanent, or behaving as if our

possessions are permanently ours, forgetting that all of them will go,

and that our so-called ownership is only relative.

- Mistaking the

impure for the pure: For

example, believing that our thoughts, emotions, opinions, or motives

in relation to ourselves, some other person, or situation are purely

good, healthy, and spiritual, when they are actually a mixture of

tendencies or inclinations.

- Confusing the

painful to be pleasureful:

For example, in our social, familial, and cultural settings there are

many actions that seem pleasure filled in the moment, only later to be

found as painful in retrospect.

- Thinking the

not-self to be the self: For

example, we may think of our country, name, body, profession, or deep

predispositions to be "who I am," confusing these with who I

really am at the deepest level, the level of our eternal Self.

Both large and small scales: As

you reflect on these forms of Avidya, you will notice that they

apply at both large scales and smaller scales, such as the impermanence of

both the planet Earth and the object we hold in our hand. The same breadth

applies to the others as well.

I am a tomato: Imagine that I said to

you, "I am a tomato." What would you think? At first, you might

smile and wait for the punch line of the joke. What if I said it again and

again, "I am a tomato." What if you came to discover that I really

believed that I am a tomato? You would probably think I was crazy and want

to have me locked up. Yet, this is exactly what we do with many aspects of

life and relationship to the objects of the world. We identify with them and

mistakenly think that, "This is 'who' I am." This is avidya,

the veiling or ignorance that prevents us from seeing clearly.

We come from a country and think we "are" that country. We say, "I

am American," or "I am Indian," etc. We follow a certain path

or teacher and say, "I am Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jew, or

Muslim." We say, "I am a daughter, son, father, mother, sister or

brother; I am the doer of this or that action; I am good or bad, I am happy

or sad." Actually, none of these are ultimately "who" I am. One who

begins to intuit that "who I am" is beyond all of these has begun

the journey of seeing beyond the ignorance called avidya, and is on

the journey to realization of the True Self, by whatever name you call that,

whether Purusha, Atman, Self, Soul or something else. It is a journey of

yoga meditation and contemplation, leading one from the ignorance or avidya

of the not-self to knowing that, which we truly are.

I am a tomato: Imagine that I said to

you, "I am a tomato." What would you think? At first, you might

smile and wait for the punch line of the joke. What if I said it again and

again, "I am a tomato." What if you came to discover that I really

believed that I am a tomato? You would probably think I was crazy and want

to have me locked up. Yet, this is exactly what we do with many aspects of

life and relationship to the objects of the world. We identify with them and

mistakenly think that, "This is 'who' I am." This is avidya,

the veiling or ignorance that prevents us from seeing clearly.

We come from a country and think we "are" that country. We say, "I

am American," or "I am Indian," etc. We follow a certain path

or teacher and say, "I am Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jew, or

Muslim." We say, "I am a daughter, son, father, mother, sister or

brother; I am the doer of this or that action; I am good or bad, I am happy

or sad." Actually, none of these are ultimately "who" I am. One who

begins to intuit that "who I am" is beyond all of these has begun

the journey of seeing beyond the ignorance called avidya, and is on

the journey to realization of the True Self, by whatever name you call that,

whether Purusha, Atman, Self, Soul or something else. It is a journey of

yoga meditation and contemplation, leading one from the ignorance or avidya

of the not-self to knowing that, which we truly are.

Avidya gets us entangled in the first

place: In relation to individual thought patterns, it is Avidya

(spiritual forgetting) that allows us to get entangled in the thought in

the first place. If in the moment the thought arises, there is also

complete spiritual awareness (Vidya) of Truth, then there is simply

no room for I-ness to get involved, nor attraction, nor aversion,

nor fear. There would be only spiritual awareness along with a

stream of impressions that had no power to draw attention into their sway.

Witnessing this Avidya (spiritual forgetting) in relation to

thoughts is the practice.

A mistake of direction:

Avidya is a sort of mistake of direction (not meaning that manifestation

of people or the universe is a mistake). One direction leads you into greater suffering, while the other

leads towards the eternal joy.

top

2.6

The coloring (klesha) of I-ness or egoism (asmita), which arises from the

ignorance, occurs due to the mistake of taking the intellect (buddhi,

which knows, decides, judges, and discriminates) to itself be pure

consciousness (purusha/drig).

(drig darshana shaktyoh ekatmata iva asmita)

- drig = consciousness

itself as seeing agent (purusha)

- darshana-shaktyoh

= the instrument of seeing, power of intellect or buddhi to observe (darshana

= seeing; shakti = power)

- ekatmata = identity,

with oneself (eka = one; atmata = selfness

- iva = appearing to be,

apparently as if

- asmita = I-ness

Finest form of individuality: Asmita

is the finest form of individuality. It is not I-am-ness, as when

we say, "I am a man or woman," or "I am a person from this

or that country." Rather, it is I-ness that has not taken on

any of those identities.

Mistake of thinking it is about me:

However, when we see I-ness or Asmita as a coloring,

a klesha, we are seeing that a kind of mistake has been made. The

mistake is that the thought pattern of the object is falsely associated

with I-ness (Asmita), and thus we say that the thought pattern is a

klishta thought pattern, or a klishta vritti. We incorrectly

come to think that this or that thought pattern is who I am.

The image in the mind is not neutral:

Imagine some thought that it is not colored by I-ness. Such

an un-colored thought would have no ability to distract your mind

during meditation, nor to control your actions. Actually, there are

many such neutral thought patterns. For example, we encounter many

people in daily life whom we may recognize, but have never met, and for

whom their memory in our mind is neither colored with attraction nor

aversion. It simply means that the image of those people is stored in

the mind, but that it is neutral, not colored.

Uncoloring your thoughts: Imagine

how nice it would be if you could regulate this coloring process

itself. Then, if there were an attraction or aversion, we

could un-color it, internally, so as to be free from its control

(or attenuate it). This is done as a part of the process of meditation. It

not only has benefits in our relationship with the world, but also

purifies the mind so as to experience deeper meditation.

I-ness is necessary for the others:

In relation to individual thought patterns, the coloring of I-ness

is necessary for attraction, aversion, and fear to

have any power. Thus, the I-ness itself is seen as a coloring

process of the thoughts. The practice is that of witnessing this Asmita

(I-ness), and how it comes into relation with though patterns.

Like the filament

confusing itself with the electricity: The klesha of asmita is like

the filament of a light bulb confusing itself with electricity. The

filament is the finest, most essential part of the light bulb, but it

still pales in comparison to the electricity that is the true source of

the light coming out of the bulb. Similarly, buddhi,

at its finest level is a very superior instrument when compared to the

other levels of mind, energy, and body. However, even buddhi is little

compared to the pure consciousness, or shakti, that is the driving force

behind not only buddhi, but all of the other, grosser levels of our being.

The coloring, or klesha of asmita (the I-ness) thinks that it is the

consciousness, forgetting the truth of the matter, and that is the mistake

that blocks Self-realization. This I-ness arises the instant that the

wave forgets (avidya) that it is also ocean.

top

2.7

Attachment (raga) is a separate modification of mind, which follows the

rising of the memory of pleasure, where the three modifications of attachment,

pleasure, and the memory of the object are then associated with one

another.

(sukha anushayi ragah)

- sukha = pleasure

- anushayi = sequential

attraction to, closely following, secondary accompaniment, resting on

- ragah = attachment,

addiction

Next arises attachments: Once

there is the primary forgetting called Avidya (2.5),

and the rising of individuality called Asmita (2.6),

there is now the potential for attachment, or Raga.

It is not that "I" am attached.

Rather, the thought is colored.

"I" then identifies with the thought.

Attachment is an obstacle, but not bad:

Raga is

not a moral issue; it is not "bad" that there is attachment.

It seems to be built into the universe and the makeup of all living

creatures, including humans.

Degree of coloring: Where we get

into trouble with attachment, is the degree of the coloring.

If the coloring gets strong enough to control us, without

restraint, we may call it addiction or neurosis, in a psychological sense.

Gaining mastery: In spiritual

practices, we want to gain mastery over the attachments. At

meditation time, we want to be able to let go of the attachments,

so that we might experience the Truth that is deeper, or on the other side

from the attachments.

Attachment is a natural habit of mind:

However, in the process of witnessing, we want to be aware of the

many ways in which the mind habitually becomes attached. If you see this

as a natural action of the mind, it is much easier to accept, without

feeling that something is wrong with your own mind. The habit of the mind

to attach can actually become amusing, bringing a smile to the face, as

you increasingly are free from the attachment.

Witnessing is necessary for meditation:

In relation to individual thoughts, attachment is one of the two

colorings that is most easily seen, along with aversion. To witness

attachments and aversions is a necessary skill to develop for meditation.

The ability to let go of the train of thoughts is based on the solid

foundation of seeing and labeling individual thoughts as being colored

with attachment.

Notice the moment just

after pleasure: Think of times just after you experience something

pleasureful. A good example is some snack food that you enjoy, such as a

sweet. Notice what happens when you put a small piece of the sweet in your

mouth. There is a burst of that delicious flavor, which brings an

emotional joy. But then, remember what happens a second or two later.

There is another emotional burst that comes right behind the enjoyment,

and that is to repeat the experience. This is the meaning of attachment,

or raga. In the definition above, anushayi is explained as being

sequential, or closely following. It is this second wave of

emotional experience, or desire, that is the attachment. It is different

from the enjoyment from the first piece of candy.

Attachment and memory:

Just like eating the sweet or candy (above), a memory of that experience

may suddenly arise at some other time. In a flash, that memory is

experienced as enjoyable. If that pleasant memory were to simply arise and

then drift away, back into the mind field from which it arose, there would

be no problem. However, just like with the original piece of candy, it

does not stop there. There is this second wave, closely following the

rising memory, in which an active desire starts to grow. This second wave

is the attachment. Once again, it is not the original enjoyment of the

sweet that caused a problem. Even the memory of that experience arise is

not, in itself, such a big problem. The problem is in that second

burst, or wave, and that is called attachment.

To witness this secondary

process during daily life and at meditation time is an extremely useful

practice to do. It provides great insight into the subtler nature of raga,

attachment. In turn, it allows a far greater level of skill in learning

non-attachment, vairagya, which is one of the two foundation practices of Yoga

(1.12-1.16). By learning to witness

the thinking process in this way, the colorings (klesha) gradually

attenuates, as was introduced in sutra 2.4 and

elsewhere.

Breaking the alliance: Three types

of modifications of mind are mentioned in this sutra: attachment, memory,

and sequence or memory. To break the alliance between these, and between

seer and seen is the key to freedom from the bondage of karma in relation

to attachment. Breaking of such alliances is discussed in upcoming sutras

(2.12-2.25).

top

2.8

Aversion (dvesha) is a modification that results from misery associated

with some memory, whereby the three modifications of aversion, pain, and the

memory of the object or experience are then associated with one another.

(dukha anushayi dvesha)

- dukha = pain, sorrow,

suffering

- anushayi = sequential

attraction to, closely following, secondary accompaniment, resting on

- dvesha = aversion or

pushing away, hatred

Aversion is a form of attachment: Aversion

is actually another form of attachment. It is what we are trying to

mentally push away, but that pushing away is also a form of connection,

just as much as attachment is a way of pulling towards us.

Aversion is just

another form of attachment.

Aversion is a natural part of the mind:

Dvesha actually

seems to be a natural part of the universal process, as we build a

precarious mental balance between the many attractions and the many

aversions.

Aversion is both surface and subtle:

It is important to remember that aversion can be very subtle, and

that this subtlety will be revealed with deeper meditation. However, it is

also quite visible on the more surface level as well. It is here, on the

surface that we can begin the process of witnessing our aversions.

Aversion can be easier to notice than

attachment: In relation to individual thought patterns, aversion

is one of the two colorings that is most easily seen, along with attachment.

Actually, aversion can be easier to notice than attachment, in that

there is often an emotional response, such as anger,

irritation, or anxiety. Such an emotional response may be mild or

strong. Because of these kinds of responses, which animate through the

sensations of the physical body, this aspect of witnessing can be

very easily done right in the middle of daily life, along with meditation

time.

Attenuating the colorings: Notice

the process of attenuating the colorings in the next section. To

follow this attenuating process, it is first necessary to be aware of the

colorings, such as aversion and attachment. Gradually,

through the attenuating process, we truly can become a witness to

the entire stream of the thinking process. This sets the stage for deeper

meditation.

Breaking the alliance: Three types

of modifications of mind are mentioned in this sutra: aversion, memory,

and sequence of memory. To break the alliance between these, and between

seer and seen is the key to freedom from the bondage of karma in relation

to aversion. Breaking of such alliances is discussed in upcoming sutras (2.12-2.25).

top

2.9

Even for those people who are learned, there is an ever-flowing, firmly

established love for continuation and a fear of cessation, or death, of

these various colored modifications (kleshas).

(sva-rasa-vahi vidushah api tatha rudhah abhiniveshah)

- sva-rasa-vahi = flowing

on its own momentum (sva = own; rasa = inclination, momentum, potency;

vahi = flowing)

- vidushah = in the wise

or learned person

- api = even

- tatha = the same way

- rudhah = firmly

established

- abhiniveshah =

resistance to loss, fear of death of identity, desire for continuity,

clinging to the life of

See also this article:

Abhinivesha section of Witnessing

your Thoughts

Protecting your false identities:

Once the ignorance or veiling of our true nature (avidya, 2.4,

2.5) has happened, and individuality (asmita, 2.6)

has arisen, along with the association with seemingly countless

attractions (raga, 2.7) and aversions (dvesha, 2.8),

there is a natural urge to protect that precarious balance of false

identities.

Two inclinations: There are two

natural inclinations after the individual false identities have been

constructed:

- Love for continuation: The

false identity is strongly held onto, even though it is a

phantom. It is perceived to be "me" even though it is a

construct of attractions and aversions. Even the aversions are clung

to as part of the balancing act of false identity.

- Fear of discontinuation: Any

perceived threat to those false identities is taken to be the threat

of cessation or death. It is not just a fear of death of the physical

body (though that might be the strongest attachment), but also the

fear of death of any of the false identities.

Nobody is exempt: It is very

common for seekers to fall into the trap of thinking that intellectual

studies and understanding is sufficient on the spiritual path. This is

particularly true in relation to practices such as described in the Yoga

Sutras, where one can do endless analysis and debate of the Sanskrit

sutras. Intellectual understanding is no protection whatsoever in relation

to these colorings (kleshas) and the natural fear that arises in relation

to their inevitable demise.

Understanding the need for uncoloring:

We are so thoroughly entangled in our attachments and aversions that even

reading about coloring and uncoloring might have little effect. We

continue to say, "But, I am this or that; I want this or that."

How often do you say, "If only I were completely free from all of my

attachments and aversions"? We tend to only want to let go of the

painful ones, while holding on to the pleasureful ones. The Yogi gradually

comes to see how even the pleasureful attachments contain the seed of pain

(2.15), and are thus to be set

aside as well (2.16), so that he or

she can truly rest in the true nature of the Self (1.3).

Wanting to keep things as they

are: Once the balance has been attained between the many attractions

and aversions, along with having the foundation I-ness and spiritual

ignorance, there comes an innate desire to keep things just the way the

are.

The resistance to losing the delicate balance

among the false identities is called

fear of the death of those identities.

Fear of change: There is a

resistance and fear that comes with the possibility of losing the current

situation. It is like a fear of death, though it does not just mean death

of the physical body. Often, this fear is not consciously

experienced. It is common for a person new to meditation to say, "But

I have no fear!" Then, after some time there arises a subtle fear, as

one becomes more aware of the inner process.

Fear is natural: This is

definitely not a matter of trying to create fear in people. Rather, it is

a natural part of the process of thinning out the thick blanket of colored

thought patterns. There is a recognition of letting go of our

unconsciously cherished attachments and aversions. When

meditation is practiced gently and systematically, this fear is seen as

less of an obstacle.

The

next sutra is 2.10

Home

Top

-------

This site is devoted to

presenting the ancient Self-Realization path of

the Tradition of the Himalayan masters in simple, understandable and

beneficial ways, while not compromising quality or depth. The goal of

our sadhana or practices is the highest

Joy that comes from the Realization in direct experience of the

center of consciousness, the Self, the Atman or Purusha, which is

one and the same with the Absolute Reality.

This Self-Realization comes through Yoga meditation of the Yoga

Sutras, the contemplative insight of Advaita Vedanta, and the

intense devotion of Samaya Sri Vidya Tantra, the three of which

complement one another like fingers on a hand.

We employ the classical approaches of Raja, Jnana, Karma, and Bhakti

Yoga, as well as Hatha, Kriya, Kundalini, Laya, Mantra, Nada, Siddha,

and Tantra Yoga. Meditation, contemplation, mantra and prayer

finally converge into a unified force directed towards the final

stage, piercing the pearl of wisdom called bindu, leading to the

Absolute.

|

|

![]() I am a tomato: Imagine that I said to

you, "I am a tomato." What would you think? At first, you might

smile and wait for the punch line of the joke. What if I said it again and

again, "I am a tomato." What if you came to discover that I really

believed that I am a tomato? You would probably think I was crazy and want

to have me locked up. Yet, this is exactly what we do with many aspects of

life and relationship to the objects of the world. We identify with them and

mistakenly think that, "This is 'who' I am." This is avidya,

the veiling or ignorance that prevents us from seeing clearly.

We come from a country and think we "are" that country. We say, "I

am American," or "I am Indian," etc. We follow a certain path

or teacher and say, "I am Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jew, or

Muslim." We say, "I am a daughter, son, father, mother, sister or

brother; I am the doer of this or that action; I am good or bad, I am happy

or sad." Actually, none of these are ultimately "who" I am. One who

begins to intuit that "who I am" is beyond all of these has begun

the journey of seeing beyond the ignorance called avidya, and is on

the journey to realization of the True Self, by whatever name you call that,

whether Purusha, Atman, Self, Soul or something else. It is a journey of

yoga meditation and contemplation, leading one from the ignorance or avidya

of the not-self to knowing that, which we truly are.

I am a tomato: Imagine that I said to

you, "I am a tomato." What would you think? At first, you might

smile and wait for the punch line of the joke. What if I said it again and

again, "I am a tomato." What if you came to discover that I really

believed that I am a tomato? You would probably think I was crazy and want

to have me locked up. Yet, this is exactly what we do with many aspects of

life and relationship to the objects of the world. We identify with them and

mistakenly think that, "This is 'who' I am." This is avidya,

the veiling or ignorance that prevents us from seeing clearly.

We come from a country and think we "are" that country. We say, "I

am American," or "I am Indian," etc. We follow a certain path

or teacher and say, "I am Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jew, or

Muslim." We say, "I am a daughter, son, father, mother, sister or

brother; I am the doer of this or that action; I am good or bad, I am happy

or sad." Actually, none of these are ultimately "who" I am. One who

begins to intuit that "who I am" is beyond all of these has begun

the journey of seeing beyond the ignorance called avidya, and is on

the journey to realization of the True Self, by whatever name you call that,

whether Purusha, Atman, Self, Soul or something else. It is a journey of

yoga meditation and contemplation, leading one from the ignorance or avidya

of the not-self to knowing that, which we truly are.