|

|

Yoga

Sutras 2.12-2.25:

Breaking

the Alliance of Karma

(Previous

Next Main)

Disconnecting seer and seen: The key to breaking the

cycle of karma is that the connection between "seer"

and that which is "seen" is set aside (2.17). This allows one to avoid

even the future karmas that have not yet manifested (2.16). Ignorance,

or avidya (2.5), is the cause of

this alliance (2.24), and eliminating this ignorance

is the means of ending the alliance (2.25). This, in

turn, breaks the cycle of karma. Disconnecting seer and seen: The key to breaking the

cycle of karma is that the connection between "seer"

and that which is "seen" is set aside (2.17). This allows one to avoid

even the future karmas that have not yet manifested (2.16). Ignorance,

or avidya (2.5), is the cause of

this alliance (2.24), and eliminating this ignorance

is the means of ending the alliance (2.25). This, in

turn, breaks the cycle of karma.

Consequences of the colorings: The

colorings (1.5, 2.3)(klishta/aklishta)

lead to birth, span of life, and experiences (2.13).

These are painful or not painful (2.14), though the

yogi comes to see them all as painful (2.15), and thus

wants to avoid these (2.16).

The subtler process of breaking the

alliance: Descriptions of the nature of the objects are given (2.18),

along with the subtle states of the elements (2.19),

and explanation of how the seer cognizes them (2.20).

It is explained that the objects exist for the benefit of the seer (2.21),

and that they cease to exist when one knows their true nature (2.22),

though continuing to be experienced by others. Even so, it is explained,

the relationship between seer and seen had to be there, so that the seer

could eventually experience the subtler truth (2.23).

Foundation: The ability to break

the alliance with karma as described in sutras 2.12-2.25 is built on a

foundation of prerequisites, including stabilizing the mind (1.33-1.39)

and minimizing the gross colorings (kleshas) of the mind (2.1-2.9).

Key is discriminative knowledge: The eight rungs of Yoga and discriminative knowledge are the key tools in this process, and are

described in the next section (2.26-2.29).

Summary of Yoga Sutras 2.12-2.25 on

Breaking the Alliance of Karma: Latent impressions that are colored

(karmashaya) result from other actions (karmas) that were brought about by

colorings (kleshas), and become active and experienced in a current life or

a future life. As long as those colorings (kleshas) remains at the root,

three consequences are produced: 1) birth, 2) span of life, and 3)

experiences in that life. Because of having the nature of merits or demerits

(virtue or vice), these three (birth, span of life, and experiences) may be

experienced as either pleasure or pain.

A wise, discriminating person sees all

worldly experiences as painful, because of reasoning that all these

experiences lead to more consequences, anxiety, and deep habits (samskaras),

as well as acting in opposition to the natural qualities. Because the

worldly experiences are seen as painful, it is the pain, which is yet to

come that is to be avoided and discarded.

The uniting of the seer (the subject, or

experiencer) with the seen (the object, or that which is experienced) is the

cause or connection to be avoided.

The objects (or knowables) are by their

nature of: 1) illumination or sentience, 2) activity or mutability, or 3)

inertia or stasis; they consist of the elements and the powers of the

senses, and exist for the purpose of experiencing the world and for

liberation or enlightenment. There are

four states of the elements (gunas), and these are: 1) diversified,

specialized, or particularized (vishesha), 2) undiversified, unspecialized,

or unparticularized (avishesha), 3) indicator-only, undifferentiated

phenomenal, or marked only (linga-matra), and 4) without indicator, noumenal,

or without mark (alingani).

The Seer is but the force of seeing itself,

appearing to see or experience that which is presented as a cognitive

principle. The essence or nature of the knowable objects exists only to

serve as the objective field for pure consciousness. Although knowable

objects cease to exist in relation to one who has experienced their

fundamental, formless true nature, the appearance of the knowable objects is

not destroyed, for their existence continues to be shared by others who are

still observing them in their grosser forms.

Having an alliance, or relationship between

objects and the Self is the necessary means by which there can subsequently

be realization of the true nature of those objects by that very Self. Avidya

or ignorance (2.3-2.5), the condition of ignoring, is the underlying cause

that allows this alliance to appear to exist.

By causing a lack of avidya, or ignorance

there is then an absence of the alliance, and this leads to a freedom known

as a state of liberation or enlightenment for the Seer.

See also these articles:

Karma and the Sources of Action, Speech, and

Thought

Archery and the Art of Reducing Karma

Coordinating the Four Functions of Mind

top

2.12

Latent impressions that are colored (karmashaya) result from other actions

(karmas) that were brought about by colorings (kleshas), and become active

and experienced in a current life or a future life.

(klesha-mula karma-ashaya drishta adrishta janma vedaniyah)

- klesha-mula = having

colorings as its origin (klesha = colored, painful, afflicted, impure;

mula = origin, root)

- karma-ashaya =

repository of karma (karma = actions stemming from the deep

impressions of samskaras; ashaya = repository, accumulation, deposit,

vehicle, reservoir, womb)

- drishta = seen, visible,

experienced consciously, present

- adrishta = unseen,

invisible, only experienced unconsciously, future

- janma = in births

- vedaniyah = to be

experienced,

Cycle of karma: The word karma

literally means actions. Here, the word karmashaya is the repository

of the effects of those actions. Usually, those individual impressions in

the repository are called samskaras.

There is a cycling process whereby the samskaras in the karmashaya rise,

cause more actions, which in turn lead to more (or stronger) samskaras in

the karmashaya.

Colorings or kleshas: The reason

for the cycling process of deep impressions and actions is the coloring or

klishta quality described in sutras 1.5

and 2.3. It bears repeating and

reflecting on many times that it is this coloring or klishta quality that

is the key to removing the blocks over Self-realization (1.3).

(See the article on klishta and aklishta

vrittis.)

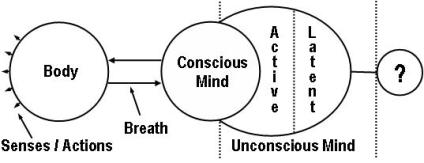

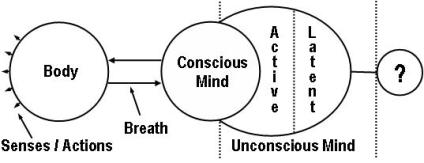

Karmashaya or repository: This

karmashaya or repository of deep impressions is in the latent

part of the mind, and later springs forth into the conscious

part of the mind, as well as the unconscious

processing part of the mind. These impressions cause the mind as manas

to carry out the actions or karmas in the external world, doing so through

the karmendriyas. (See the article on levels

and domains of consciousness.)

Actions come at any time: The

timing of the playing out of these actions is varied. It may come in the

present or seen (drishta) birth (janma), or it may come in later or unseen

(adrishta) births. In the meantime, the coloring or klishta of the

samskaras (karmashaya) may remain completely dormant, or it may play out

in the unconscious dream state.

See also the article:

Karma and the sources of Actions, Speech, and Thoughts

top

2.13

As long as those colorings (kleshas) remains at the root, three

consequences are produced: 1) birth, 2) span of life, and 3) experiences

in that life.

(sati mule tat vipakah jati ayus bhogah)

- sati = since being here,

being present, existing

- mule = to be at the root

- tat = of that

- vipakah = ripening,

fruition, maturation

- jati = type of birth,

species, state of life

- ayus = span of life,

lifetime

- bhogah = having

experience, resulting enjoyment

Colorings lead to

three consequences: The entire principle of karma (which literally

translates as actions) is that the deep impressions (samskaras) that are

colored (klishta) leads to the further playing out of karma. That karma is

of three kinds:

- Type of birth: First, those colored

impressions lead you to this or that type of birth, in this or that

circumstance.

- Span of life: Second, there is a

built-in span of life programmed in, though that span can be altered

by decisions and actions during life.

- Experiences: Third, you will quite

naturally have many experiences related to those impressions as they

become active and play themselves out.

Altering the samskaras:

Describing this process is

setting the stage for the means of altering these deep impressions. The

point of this sutra is that these consequences play out only as long as

the root samskaras are there, and that they remain colored (klishta). If

the coloring is reduced or removed (aklishta), then the consequences are

altered.

Remember, once again, the

foundation principle of Yoga has to do with these colorings, as was first

presented in Chapter 1, in sutra 1.5)

top

2.14

Because of having the nature of merits or demerits (virtue or vice), these

three (birth, span of life, and experiences) may be experienced as either

pleasure or pain.

(te hlada-paritapa-phalah punya apunya hetutvat)

- te = they, those

(referring to those who take birth, as in the last sutra)

- hlada-paritapa-phalah =

experiencing pleasure and pain as fruits (hlada = pleasure, delight;

paritapa = pain, agony, anguish; phalah = fruits)

- punya = virtuous,

meritorious, benevolent

- apunya = non-virtuous,

vice, bad, wicked, evil, bad, demerit, non-meritorious

- hetutvat = having as

their cause (the punya or apunya)

There are three major parts in this short

sutra, and each are important:

- Three consequences of birth, span of

life, and experiences come as a result of the karmashaya (samskaras)

mentioned in the previous sutra (2.13).

- Those samskaras (karmashaya) were imbued

with the nature of either merit or demerit (punya/apunya), virtue or

vice.

- Resulting from that, the play out or

actions (karma) from those impressions might be experienced as either

pain (paritaba) or pleasure (hlada).

Three consequences: The playing

out of the kleshas (colored impressions or samskaras) mentioned in the

previous sutra (2.13) will lead to experiences of one

form or another. They will not just remain inert, and will not just go

away. They will definitely lead to some experiential effect. These deep

impressions are so strong that they will also lead to birth. Thus, it has

been said that desire is stronger than death, in that it causes rebirth. A

part of the play out of the karmashaya is also that a certain duration

comes along. This can make sense by simply reflecting on the notion that

stronger drives logically last longer than weaker ones.

Merit or demerit: Though not

purely accurate, it has become commonplace to speak of good karma

or bad karma. In a broad sense, this is the meaning of punya

and apunya. It means that when our actions lead to deep impressions

or samskaras, they are either of a type or nature that leads in a

positive, useful direction, or in a negative, un-useful direction. The

nature of this merit or demerit (virtue or vice) goes along with the

samskara itself, in that the samskara leads to the action, and this

secondary quality comes along.

Notice that cultivating punya versus

apunya is one of the stabilizing practices introduced in sutra 1.33.

Pain or pleasure: Once the future

action starts to play out as a result of the samskaras (karmashaya), the

issue of merit or demerit will cause the actions to be experienced as

either pain (paritaba) or pleasure (hlada).

Planning your karma: By

understanding this process, it becomes clear that ones actions can be

planned in such a way that future karma is determined. This is described

further in the next few sutras.

top

2.15

A wise, discriminating person sees all worldly experiences as painful,

because of reasoning that all these experiences lead to more consequences,

anxiety, and deep habits (samskaras), as well as acting in opposition to

the natural qualities.

(parinama tapa samskara duhkhaih guna vrittih virodhat cha duhkham eva

sarvam vivekinah)

- parinama = of change,

transformation, result, consequence, mutative effect, alteration

- tapa = anxiety, anguish,

pain, suffering, misery, torment

- samskara = subtle

impressions, imprints in the unconscious, deepest habits

- duhkhaih = by reason of

suffering, sorrows

- guna = of the qualities,

gunas of prakriti (sattvas, rajas, tamas)

- vrittih = operations,

activities, fluctuations, modifications, changes, or various forms of

the mind-field

- virodhat = because of

reasoning the contradictory

- cha = and

- duhkham = because of the

pain, suffering, sorrow

- eva = is only

- sarvam = all

- vivekinah = to one who

discriminates, discerns

Discrimination comes in time:

Seeing all worldly experiences as painful is not a mere opinion or belief

system that one cultivates because of following some certain spiritual

path. Rather, it comes from the process of discrimination, and this takes

time and practice. By repeatedly seeing the process of the playing out of

samskaras (karmashaya), leading to more deep impressions, and again

recycling, the Yogi comes to conclude for himself or herself that the

entire process is bringing nothing but pain in the long run.

Wisdom, not depression: To simply

read this, that everything worldly brings pain, can seem rather depressing

or fatalistic. This is definitely not the case. This insight comes with

wisdom, with seeing clearly the nature of the temporal process. The Yogi

feels a sense of joy in this insight, as it causes an even greater drive

towards Self-realization, the direct experience of that eternal Self,

which is not subject to change, death, decay, or decomposition.

Name and form of the prime elements:

The Yogi comes to see that the primal elements or gunas (sattvas, rajas,

and tamas) just keep changing names and forms. It is that incessant

transitioning process that is seen to be not worthy of continuing

unabated. Eventually, through the practices of Yoga, the gunas themselves

are resolved back into their cause, leading to liberation (4.32-4.34).

Going in the wrong direction: The

Yogi also comes to see that all of these activities are outward bound,

moving directly in the opposite direction from the eternal Self. Because

of that insight, he or she wants even more strongly to go inward, in

pursuit of the direct experience of pure consciousness, or Purusha

(3.56, 4.34).

top

2.16

Because the worldly experiences are seen as painful, it is the pain, which

is yet to come that is to be avoided and discarded.

(heyam duhkham anagatam)

- heyam = to be discarded,

avoided, prevented

- duhkham = pain,

suffering, sorrow

- anagatam = which has not

yet come, in the future

Currently manifesting: The three

consequences of birth, span of life, and experiences (2.13)

may be playing out in the current time or life, and may be experienced as

pain or pleasure (2.14). One has to deal with these

impressions and their actions (karmas) in the here and now.

Manifesting later: Other samskaras

of the karmashaya (2.12) are not driven by their

current coloring or life circumstance to play out at the present moment.

They remain in their latent form in the latent

part of the mind, destined to come to life and play out later.

Explore the latent: The Yogi comes

to the point of practices where it is not only the currently manifesting

karmas that are dealt with. Rather, he or she intentionally explores the unconscious

processing part of the mind and the latent

part of the mind, so as to uncover, attenuate, and eliminate the

coloring (klishta) (1.5,

2.3) of these deep impressions, as

was described in sutra 2.4. In this

way, the effects (karma) of those deep

impressions are discarded, avoided, or prevented (hevam). Then the absolute

or pure consciousness behind the veil can be experienced.

As sensitive as the surface of the

eyeball: In describing how the Yogi wants to avoid the pain that is

still to come, the commentator Vyasa says that the Yogi's perception has

become as sensitive as the surface of an eye-ball. It is because of this

highly refined sense of self-awareness that he or she discovers the future

karmas in the karmashaya, and wants to deal with them long before they

have the chance to come to fruition.

The seer and the seen: The key to

this process of avoiding future karmas is breaking the tie between the

seer and the seen (2.17), as described in the

remaining sutras of this section.

top

2.17

The uniting of the seer (the subject, or experiencer) with the seen (the

object, or that which is experienced) is the cause or connection to be

avoided.

(drashtri drishyayoh samyogah heya hetuh)

- drashtri = of the seer,

knower, apprehender

- drishyayoh = of the

seen, knowable

- samyogah = union,

conjunction

- heya = to be discarded,

avoided, prevented

- hetuh = the cause,

reason

The seer engulfs the seen:

Connecting the seer with the seen does not mean the physical eyes looking

at physical objects. It means the pure consciousness (1.3,

2.20) wrapping itself

around the subtlest of the traces in the deep unconscious. Those deep

impressions (samskaras) are engulfed (1.4)

by consciousness, and then the forgetting process of avidya (2.5,

2.24) becomes even more pronounced. The subtler nature of these seen objects

is described in the next few sutras, below. (Click

here for more info on the process of the observer observing the

observed.)

The key is in loosening

the alliance: The key here is that, in a moment when the seer is not

connected with any of those possible seen objects, there is

freedom, and that is the higher state of consciousness that is being

sought (1.3, 4.26). However, it comes in stages. Layer after layer, object after

object, the seer is loosened from its connection to the seen. This is why

there is progress on the inner journey, and it is a progress that comes

from revealing and setting aside, so as to uncover the true Self at the

center.

Samskaras become mere

memories: In the foundation principles of sutra 1.5,

it was described that thought patterns are one of five kinds, and that

these are either klishta or aklishta

(colored or uncolored). One of those

five kinds of thought patterns is that of memory. Here, in this current

sutra (2.17), the fulfillment of that process is being described, wherein

the colored thought processes become mere memories that are no longer

colored by any of the five kleshas (2.3).

The final alliance is

broken: The rest of this chapter, and the sutras of Chapter 3 further

describe the process of breaking the alliances. After fully describing the

process of how the many alliances are progressively loosened, sutras 2.25

and 3.50 (end of the next chapter)

describe how the final disconnect happens with the renunciation of avidya

itself, and of the alliance between buddhi and consciousness. This means

that even the finest instrument of knowing is ultimately set aside from

consciousness itself .

top

2.18

The objects (or knowables) are by their nature of: 1) illumination

or sentience, 2) activity or mutability, or 3) inertia or stasis; they

consist of the elements and the powers of the senses, and exist for the

purpose of experiencing the world and for liberation or enlightenment.

(prakasha kriya sthiti shilam bhuta indriya atmakam bhoga apavarga artham

drishyam)

- prakasha = illumination,

light

- kriya = of activity

- sthiti = steadiness,

inertia, stasis

- shilam = having the

nature of (illumination, activity, steadiness)

- bhuta = the elements

(earth, water, fire, air, space)

- indriya = powers of

action and sensation, instruments, mental sense organs

- atmakam = consisting of

(elements and senses)

- bhoga = experience,

enjoyment

- apavarga = liberation,

freedom, emancipation

- artham = for the sake

of, purpose of, object of

- drishyam = the seen, the

knowable

Understanding the seer and the seen:

It is essential to have some understanding of the nature of the seer

and of the seen if we are to be able to understand the nature of

the alliance between them, and how to break that alliance. Describing the

nature of the seer and the seen is the subject of this and

the next few sutras. Here, in this sutra, that nature of the seen

is briefly described as being part of several categories or types. The

seer is described in sutra 2.20.

Three broad types of seen

objects: Based on the three gunas, or primary constituent elements,

objects have a tendency towards one or the other of three types. These are

objects predominantly of prakasha (illumination, light), kriya (activity),

or stithi (steadiness, inertia, stasis). The four states of these elements

(2.19), the purpose of these knowable objects (2.18),

the reason for the seer's alliance with them (2.23),

and the means of freedom (2.25) are explained in the

following sutras of this section.

Five elements as objects of meditation: The seen objects

are composed of the five elements (indriyas)

of earth, water, fire, air, and space (bhutas). The many manifestations of

these, as well as the five elements as individual entities are examined

with the razor-sharp discrimination of samyama (3.4-3.6),

and are set aside with non-attachment (1.16).

Mastery over the five elements comes through direct examination of their

nature (3.45), with the fruits

being renounced (3.38). This process

of examining the objects and the elements leads ever closer towards the

seer resting in its true nature (1.3).

Five indriyas as objects of meditation: Along with those

many objects and the five elements, there comes the five instruments (indriyas)

of action (karmendriyas) and

sensation (jnanendriyas). After

first training the senses (2.32, 2.43),

these ten means of expression and perception are themselves examined as

objects (3.48). Through samyama (3.4-3.6),

the ten senses themselves are also set aside with non-attachment (1.16),

adding to the movement towards the seer resting in its true nature (1.3).

Beyond conventional objects:

At some stage of the subtler journey within, we examine not only objects

and mental impressions in the conventional sense. We also explore both

the components that build those objects (bhutas of earth, water, fire,

air, and space), and the senses themselves (ten

indriyas). Through such subtle practice, awareness moves past all of

the objects in the conventional sense. It is starting the process of observing

the observing process, which is of critical importance in the

journey to realization of the observer itself (1.3).

top

2.19

There are four states of the elements (gunas), and these are: 1)

diversified, specialized, or particularized (vishesha), 2) undiversified,

unspecialized, or unparticularized (avishesha), 3) indicator-only,

undifferentiated phenomenal, or marked only (linga-matra), and 4) without

indicator, noumenal, or without mark (alingani).

(vishesha avishesha linga-matra alingani guna parvani)

- vishesha = diversified,

specialized, particularized, having differences

- avishesha =

undiversified, unspecialized, unparticularized, having no differences

- linga-matra =

undifferentiated, only a mark or trace (linga = mark, trace; matra =

only)

- alingani = without even

a mark or trace, undifferentiated subtle matter

- guna-parvani = state of

the gunas (guna = of the qualities, gunas of prakriti; parvani =

state, stage, level)

Elements evolve and involve in four

stages: All of the objects and elements mentioned in the last sutra

(2.18) are constituted of the three primal elements (gunas). As the

attention of the Yogi goes deeper and deeper into the gunas, they are seen

to evolve and involve in four stages. Gradually the Yogi

fathoms each of these very subtle processes. This allows the seer to

systematically break the connection with the seen, as described in sutra 2.17.

- Vishesha = diversified,

specialized, particularized, having differences

- Avishesha =

undiversified, unspecialized, unparticularized, having no differences

- Linga-matra =

undifferentiated, only a mark or trace (linga = mark, trace; matra =

only)

- Alingani = without even

a mark or trace, undifferentiated subtle matter

Supreme non-attachment: Practice

and non-attachment have been introduced as two foundations of Yoga (1.12-1.16).

Supreme non-attachment (paravairagya) was described as non-attachment even

to the gunas, the subtlest elements, constituent principles, or qualities

themselves (1.16). These gunas are

the subject of this current sutra.

top

2.20

The Seer is but the force of seeing itself, appearing to see or experience

that which is presented as a cognitive principle.

(drashta drishi matrah suddhah api pratyaya anupashyah)

- drashta = the seer

- drishi-matrah =

power of seeing (drishi = seeing; matrah = power)

- suddhah = pure

- api = even though,

although

- pratyaya = the cause,

the feeling, causal or cognitive principle, notion, content of mind,

presented idea, cognition

- anupashyah = appearing

to see

Understanding the seer and the seen:

As was pointed out above (2.18), it is essential to

have some understanding of the nature of the seer and of the seen

if we are to be able to understand the nature of the alliance between

them, and how to break that alliance. Describing the nature of the seer

is the subject of this current sutra, and of the seen is the

subject of the next few sutras.

Who makes the alliance?: If we are

trying to break the alliance between seer and seen (2.17,

2.12-2.25), then who is the seer who has

made that false alliance? It is the pure consciousness known as purusha,

atman, or Self. It is that, which remains (1.3)

after the mastery (nirodah, 1.2) of

the many impressions in the mind field.

Nature of the objects of alliance:

If the seer is pure consciousness, then what is the nature of those

objects (1.4) with which the false

alliance has occurred? The nature of those objects is described in the

next sutra (2.21).

top

2.21

The essence or nature of the knowable objects exists only to serve as the objective field for pure consciousness.

(tad-artha eva drishyasya atma)

- tad-artha = the purpose for

that, to serve as (tad = that; artha = purpose)

- eva = only

- drishyasya = of the

seen, knowable

- atma = essence,

being, existence

Relationship between seer and seen:

While there are countless objects, it is useful to know that all objects

share one thing in common. They are all witnessed by the seer, the

Self, or pure consciousness. Thus, the nature of the relationship between

consciousness and one object is similar to the relationship between

consciousness and any other object--they both share the same observer or

seer.

Breaking the alliance is similar:

If the nature of the alliances is similar, then the means of breaking

those alliances is also similar. This means that there is a basic

simplicity in the process of discrimination (2.26-2.29)

that leads to Self-realization. This doesn't make the process easy,

but it sure is useful to see the underlying simplicity in the

process. Regardless of what object is seen by the seer, and regardless of

its coloring (klishta), the means of seeing clearly through discrimination

is similar in all cases. Thus, the Yogi keeps doing the same basic process

of examining, discriminating, and setting aside with non-attachment (1.12-1.16).

Over and over, through all the levels of concentration (1.17),

and with each of the kinds of coloring (2.4),

the same means of razor-like discrimination occurs (3.4-3.6).

top

2.22

Although knowable objects cease to exist in relation to one who has

experienced their fundamental, formless true nature, the appearance of the

knowable objects is not destroyed, for their existence continues to be

shared by others who are still observing them in their grosser forms.

(krita-artham prati nashtam api anashtam tat anya sadharanatvat)

- krita-artham = one whose

purpose has been accomplished (krita = accomplished; artham = purpose)

- prati = towards, with

regard to

- nashtam = ceased,

dissolved, finished, destroyed

- api = even, although

- anashtam = has not

ceased, not dissolved, not finished, not destroyed

- tat = that

- anya = for others

- sadharanatvat = being

common to others, due to commonness

Objects cease to exist: As

attention moves subtler and subtler through the layers of existence, those

objects that were there for the benefit of the seer (2.21)

no longer exist for the seer. A most simple example of this is when one's

attention turns inward, even for the beginning meditator. At first, the

external world and its sounds are a distraction. Yet, suddenly, when

attention actually moves inward, it is as if the external world, its

objects, and people cease to exist. When attention moves inward, down

through the levels of manifestation of earth, water, fire, air, and space,

for example, those levels also cease to exist for the seer.

Objects continue for others: While

the objects cease to exist for the Yogi, they continue to exist for

others. For example, in case of the meditator mentioned above, the

external world ceases for that person, but continues for others. The same

is also true for the subtler aspects such as the elements and indriyas (2.18).

top

2.23 Having

an alliance, or relationship between objects and the Self is the necessary

means by which there can subsequently be realization of the true nature of

those objects by that very Self.

(sva svami saktyoh svarupa upalabdhi hetuh samyogah)

- sva = of being owned

- svami = of being owner,

master, the one who possesses

- saktyoh = of the powers

- svarupa = of the nature,

own nature, own form (sva = own; rupa = form)

- upalabdhi = recognition

- hetuh = that brings

about, the cause, reason

- samyogah = union,

conjunction

Alliance was necessary to know objects:

If the alliance between the seer and the seen had never happened, it would

not be possible for the seer to have objective knowledge. Later, as

practices unfold, that so-called knowledge is seen to be based on

ignorance (avidya, 2.5), and thus,

is seen to be not knowledge after all.

Alliance allows breaking the alliance:

Furthermore, having that false alliance between seer and seen

allows one to seek, and to find the true Self (1.3).

Had there been no alliance, this journey would not have been possible. In

other words, the alliance itself (between seer and seen) was an essential

prerequisite! Thus, it is sometimes said that the entire universe is all lila, or play.

top

2.24

Avidya or ignorance (2.3-2.5),

the condition of ignoring, is the underlying cause that allows this

alliance to appear to exist.

(tasya hetuh avidya)

- tasya = of that (of that

alliance, from last sutra)

- hetuh = that brings

about, the cause, reason

- avidya = spiritual

forgetting, ignorance, veiling, nescience

How the alliance arose in the first

place: All of the alliances between seer and seen, which have been

described in the previous few sutras (begin 2.17),

were able to arise because of the foundation klesha (coloring) (1.5,

2.3) of avidya, or ignorance (2.5).

Without that primary foundation, the other alliances simply could not have

grown. It is somewhat like saying the walls and roof of a house could not

be built without a foundation, or that plants could not grow without some

form of soil or substratum in which to grow.

Neutralize the foundation: By

neutralizing or eliminating the foundation of avidya or ignorance (2.5),

all of the would-be alliances are effectively dealt with. This is

described in the next sutra (2.25).

top

2.25

By causing a lack of avidya, or ignorance there is then an absence of the

alliance, and this leads to a freedom known as a state of liberation or

enlightenment for the Seer.

(tat abhavat samyogah abhavah hanam tat drishi kaivalyam)

- tat = its

- abhavat = due to its

disappearance, lack or absence (of that ignorance in the last sutra)

- samyogah = union,

conjunction

- abhavah = absence,

disappearance, dissolution

- hanam = removal,

cessation, abandonment

- tat = that

- drishi = of the knower,

the force of seeing

- kaivalyam = absolute

freedom, liberation, enlightenment

Causing an absence of ignorance:

There is an important subtle point here that is very practical. By removal

of the ignorance (avidya) (2.5),

there remains a void, absence, or lack of avidya. It is this absence of

avidya (ignorance) that is desired, not just the act of eliminating it. If

we say that our goal is eliminating avidya, it sets the stage for the mind

to continue to produce ignorance or misunderstanding, so that we can

fulfill our goal of eliminating it. If we want to take on the false

identity of being an eliminator of ignorance, then more and more ignorance

will be produced, so that we may fulfill the desire of eliminating.

However, if we have the stated goal of the absence of ignorance,

our mind will become trained to seek that state of absence of avidya. The

elimination of ignorance becomes the process along the way towards that

eventual final goal (4.30).

Freedom beyond ignorance: With

avidya or ignorance (2.5) seen as

the foundation or soil out (2.24) of which grows the

many alliances of seer and seen (2.17), we see one of

the key points of all sadhana (spiritual practices), that of moving beyond

the misperceptions of avidya, of which there are four major forms (2.5):

1) regarding that which is transient as eternal, 2) mistaking the impure

for pure, 3) thinking that which brings misery to bring happiness, and 4)

taking that which is not-self to be self.

Discrimination is the tool: Over

and over, with our razor-like discrimination, we set aside the alliances

between seer and seen (2.17),

seeing beyond the four forms of avidya

(2.5).

This constitutes breaking the alliance of karma. This process of

discrimination is described in the next (2.26-2.29)

and later (3.1-3.3, 3.4-3.6)

sutras.

The

next sutra is 2.26

Home

Top

-------

This site is devoted to

presenting the ancient Self-Realization path of

the Tradition of the Himalayan masters in simple, understandable and

beneficial ways, while not compromising quality or depth. The goal of

our sadhana or practices is the highest

Joy that comes from the Realization in direct experience of the

center of consciousness, the Self, the Atman or Purusha, which is

one and the same with the Absolute Reality.

This Self-Realization comes through Yoga meditation of the Yoga

Sutras, the contemplative insight of Advaita Vedanta, and the

intense devotion of Samaya Sri Vidya Tantra, the three of which

complement one another like fingers on a hand.

We employ the classical approaches of Raja, Jnana, Karma, and Bhakti

Yoga, as well as Hatha, Kriya, Kundalini, Laya, Mantra, Nada, Siddha,

and Tantra Yoga. Meditation, contemplation, mantra and prayer

finally converge into a unified force directed towards the final

stage, piercing the pearl of wisdom called bindu, leading to the

Absolute.

|

|