|

Home Site Map CDs Inviting Thoughts Summary page Colored thoughts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Witnessing

Your Thoughts Witnessing the flow of mind: Witnessing your thoughts is a most important aspect of Yoga practice. Witnessing the thought process means to be able to observe the natural flow of the mind, while not being disturbed or distracted. This brings a peaceful state of mind, which allows the deeper aspects of meditation and samadhi to unfold, revealing that which is beyond, which is Yoga or Unity.

Contents of this web page: See also these

articles: Introduction Simple and complex: The process of witnessing your thoughts and other inner processes is elegantly simple once you understand and practice it for a while. However, in the meantime it can admittedly seem quite complicated. In the writing of this article the intent is simplicity, though the length of the article makes it appear complicated. If we hold in mind the paradox of the simple appearing complex, then it is much easier to practice witnessing, and then allow it to gently expand over time. Most of the aspects of witnessing described below are in Yoga (see Yoga Sutras) and Vedanta, although they are universal processes that are also described elsewhere. A simple process: Witnessing starts with an extremely simple process of 1) observing individual thoughts, 2) labeling them as to their nature, and then, 3) letting go of any clinging to those thoughts, so as to dive deep into the still, silent consciousness beyond the mind and its thinking process. (See also the page on inviting thoughts.)

It would also be useful to explore the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, particularly the first part of Chapter 1, the first part of Chapter 2, and the notes on witnessing. Both in daily life, and during meditation: It is extremely important to know that you can do much of the witnessing practice in daily life, right in the middle of your other activities. You will surely want to do this at meditation time as well, but tremendous progress can be made without having to set aside a single minute of extra time for this practice. You do it while you are doing your service to others.

What does labeling and witnessing mean? Simply observe: Labeling your thoughts is an extremely simple process of observing the nature of your thought process in a given moment. (The basic principle is so simple that it is easy to make the mistake of not doing it!) What's useful and not useful: A simple and obvious example will help. If you have a negative thought about yourself or some other person, a thought that is not useful to your growth, you simply notice it and note that, "This is Not Useful" silently saying the words internally. Or, you may internally say only the single phrase, "Not Useful". Negative thoughts can continue to control us only when we are not aware of them. When we notice them, and label them as "Not Useful" thoughts, we can deal with those thoughts in positive, useful ways. (See Yoga Sutras, particularly the notes on discrimination) See your thoughts honestly: This is not being negative about yourself, passing judgment on yourself, or calling yourself negative. Rather, it is a process of honestly naming the thought pattern for what it is, a negative thought. Such observation is not a guilt-ridden passing judgment, but rather, a healthy form of adjudging a situation, in this case, that the thought is negative.

Remind yourself what is useful or not useful: What about the positive thoughts? Similarly, when positive, helpful thoughts arise that lead us in the direction of growth and spiritual truths or enlightenment, we can remind ourselves, "This is Useful," or simply, "Useful". Then we can allow those useful thoughts move into actions. This reminding process becomes non-verbal: After some time of doing such a practice, you will naturally find that the labeling process becomes non-verbal. It is very useful to literally say the words internally when you label the thoughts. However, the non-verbal labeling comes automatically as you increasingly become a witness to your thought process. During meditation, the thoughts can then easily come and drift away. (This means the mind is awake and alert, as well as clear, which is not meaning dull, lethargic, or in a trance.) Label and go beyond the thoughts: Yoga science maps out many aspects of the mental process so that the student of yoga meditation can encounter, deal with, and eventually go beyond the entire thought process to the joy of the center of consciousness. We learn to label the thoughts, and then gradually learn to go beyond them. (Some of the types of thoughts to witness are described below in this paper. Also, a summary page has been written, so that you can print this out as an aid to study and practice.) Parts to the process of witnessing: Witnessing the thought process means to be able to: 1) observe the natural flow of the mind, and 2) notice the nature of the thought patterns, 3) while not being disturbed or distracted by this mental process. There is a simple formula to this process:

Weaken the grip of samskaras: When one can begin to witness the thought process, meditation can be used as a means to weaken (Yoga Sutra 2.4) the grip of the deep impressions called samskaras, the driving force of actions or karma. Then, the deeper aspects of meditation are accessible. Training your own mind: It is important to remember that there is another aspect of labeling and witnessing that has to do with the direct training of your mind. This is the process of deciding and training your mind whether a given thought is Useful or Not Useful (This was mentioned above, and is covered later in the paper, after introducing all of the thought processes). Why should I label my thoughts? Labeling and witnessing is spiritual practice: In Yoga meditation science one becomes a witness of the thought process, including all of the various types of inner activity. The practice of consciously labeling and witnessing the thought patterns is an extremely useful aspect of spiritual practice. Such self-training sets the stage for moving beyond the entire mental process to the Self, the Center of Consciousness.

Encounter, explore, train, and transcend mind: Between where we are and Self-Realization stands the mind. To attain the direct experience of the Self, which is beyond the mind, we must encounter and explore the mind itself, so as to transcend it. Even a cursory review of the Yoga Sutras reveals that it is an instruction manual on how to examine and train the mind, so as to go beyond. Learning to use the simple tool: When we learn to ride a bike, drive a car, or use a computer, there is a learning process of how to use the tools. Once the tools are understood and used for a while, the process becomes quite simple. Self-observation is also a tool that is quite simple, once it is used for a while, and some understanding comes. Then, by identifying or labeling our thought process, we can then witness the whole stream of mind. Am I ready and willing to explore my thoughts? Preparation is needed: Patanjali describes the process of Yoga meditation in the Yoga Sutras, and the first word is Atha which means now, then, and therefore (sutra 1.1). It is a particular word for Now that implies prior preparation. It means that one is prepared to tread the path of self-exploration through Yoga meditation.

Are you willing to explore within?: The first question about your state of mind is to ask yourself if you are willing to explore your own thoughts and thought process. It does not mean a perfect or absolute readiness and willingness, but it does mean having an attitude in which there is a sincere intent to move inward. The problem comes when we don't want to do this, saying to ourselves that such inner exploration is not needed for the spiritual journey. This is one of the main reasons that so many people practice so-called meditation for years and decades, yet privately complain of not making progress. Following the preliminary steps: We simply must be willing to encounter and explore the mind if we are to progress beyond it to the direct experience of the Self. If we are not prepared to do this, we are not truly ready to tread the path of Yoga meditation. One who is not presently willing to explore within and is not ready to do these practices, may find that more preliminary steps leading to Yoga meditation are more useful. Eventually these may lead one to the deeper aspects of Yoga science.

The mind is inescapable: However, ultimately one must face his or her own thought process. There is no other way, as the mind stands between our surface reality and the deepest inner Truth. The methods may be somewhat different on different paths, but encountering and dealing with the mental process is inescapable. Desire for truth swallows other desires: If the "Yes" to the willingness to explore the thoughts and thought process is even a small "Yes," then one can nurture that small flame of desire until it is a forest fire of desire to know the Self. That single-minded desire for Truth swallows up the smaller desires and opens the door for the grace which guides from within.

Developing burning desire, sankalpa shakti: This burning desire to know, with conviction is called Sankalpa Shakti. Many people hear of and say they want the awakening of Kundalini Shakti, the spiritual energy within. However, the first form of Shakti, or energy, to cultivate is that of Sankalpa, or determination. It means cultivating a deep conviction to know oneself at all levels, so as to know the Self at the core. It means having an attitude that, "I can do it! I will do it! I have to do it!" (See Yoga Sutra 1.20 on efforts and commitments) I am not my thoughts Who I am, is beyond the mind: The fact that "I am not my thoughts" is one of the most fundamental and important of all principles of Yoga science. This is actually the way in which Patanjali introduces Yoga in the first four instructions of the Yoga Sutras. Paraphrasing, he says:

Not merely blind faith: If we only believe this, or have blind faith in this principle, then we will miss the opportunity for the direct experience of this reality.

Find out for yourself: In the oral tradition of Yoga meditation, it is said that you should never just believe what you read or are told, but that you should also not reject these things either. Rather, take the principles, reflect on them, do the practices, and find out for yourself, in direct experience whether or not they are true. Repeating the same discovery: The means of doing this, in this case, is to systematically explore all of the levels of the thinking process, one at a time. Repeatedly you will discover, "Who I am, is different from this particular thought pattern that I am witnessing right now!" Over and over this insight will come, in direct experience, thought after thought, impression after impression. Owning your own truth: Gradually, you come to see in your own opinion, observation, conclusion, and experience that, "I am not any of these thoughts!" Then you own it as your own experience and truth. Direct experience is the goal: Good or bad, happy or sad, clear or clouded, none of the thoughts are who we are. It is no longer a theory from some book, or the mere statement of some other person, however great that person may be. This kind of direct experience is the goal spoken of by the ancient Yogis, Sages and Masters of the Himalayas. It comes when the practices of meditation, contemplation, prayer, and mantra converge in one experience of pure witnessing. Personality is a perfect expression: Resting in this realization, we also come to see that the habit patterns which define our personality are perfect expressions of this individual person. The beauty of our personality uniqueness is seen, ever more clearly, as we remember our True Self that is beyond, yet always there. (Yoga Sutra 1.3) Witnessing the indriyas or ten senses Like a building with ten doors: The human being is like a building with ten doors. Five are entrance doors, and five are exit doors. Witnessing these ten senses is an important part of meditation, and meditation in action. Ten senses: The ten indriyas or active and cognitive senses are:

See also the separate article entitled Training the Ten Senses or Indriyas, which includes three sections on witnessing the ten senses in daily life and at meditation time:

Which of five states is your mind in right now? From Yoga Sutra 1.1: The first Sutra of the Yoga Sutras says, "Now, after having done prior preparation through life and other practices, the study and practice of Yoga begins" (atha yoga anushasanam). The word atha is used for now, and this particular word implies a process of preparation, or stages, which one needs to move through before being able to practice yoga meditation at its fullest level. The sage Vyasa describes five states of mind, which range from the severely troubled mind to the completely mastered mind. It is very useful to be aware of these stages, both in the moment, and as a general day-to-day level at which one is functioning. It reveals the depth of practice that one might be able to currently practice. Some aspect of yoga meditation applies to every human being, though we need to be mindful of which is most fitting and effective for a person with this or that state of mind. Two of the states are desirable: Of the five states of mind (below), the later two of which are desirable for the deeper practice of yoga meditation. For most people, our minds are usually in one of the first three states. Stabilize the mind in one-pointedness: By knowing this, we can deal with our minds so as to gradually stabilize the mind in the fourth state, the state of one-pointedness. This is the state of mind which prepares us for the fifth state, in which there is mastery of mind. (The first two states might also be dominant or intense enough that they manifest as what psychologists call mental illness.)

1. Kshipta/disturbed: The ksihipta mind is disturbed, restless, troubled, wandering. This is the least desirable of the states of mind, in which the mind is troubled. It might be severely disturbed, moderately disturbed, or mildly disturbed. It might be worried, troubled, or chaotic. It is not merely the distracted mind (Vikshipta), but has the additional feature of a more intense, negative, emotional involvement. 2. Mudha/dull: The mudha mind is stupefied, dull, heavy, forgetful. With this state of mind, there is less of a running here and there of the thought process. It is a dull or sleepy state, somewhat like one experiences when depressed, though we are not here intending to mean only clinical depression. It is that heavy frame of mind we can get into, when we want to do nothing, to be lethargic, to be a couch potato. The Mudha mind is barely beyond the Kshipta, disturbed mind, only in that the active disturbance has settled down, and the mind might be somewhat more easily trained from this place. Gradually the mind can be taught to be a little bit steady in a positive way, only occasionally distracted, which is the Vikshipta state. Then the mind can move on in training to the Ekagra and Nirrudah states. 3. Vikshipta/distracted: The vikshipta mind is distracted, occasionally steady or focused. This is the state of mind often reported by students of meditation when they are wide awake and alert, neither noticeably disturbed nor dull and lethargic. Yet, in this state of mind, one's attention is easily drawn here and there. This is the monkey mind or noisy mind that people often talk about as disturbing meditation. The mind can concentrate for short periods of time, and is then distracted into some attraction or aversion. Then, the mind is brought back, only to again be distracted. The Vikshipta mind in daily life can concentrate on this or that project, though it might wander here and there, or be pulled off course by some other person or outside influence, or by a rising memory. This Vikshipta mind is the stance one wants to attain through the foundation yoga practices, so that one can then pursue the one-pointedness of Ekagra, and the mastery that comes with the state of Nirrudah. 4. Ekagra/one-pointed: The ekagra mind is one-pointed, focused, concentrated (Yoga Sutra 1.32). When the mind has attained the ability to be one-pointed, the real practice of Yoga meditation begins. It means that one can focus on tasks at hand in daily life, practicing karma yoga, the yoga of action, by being mindful of the mental process and consciously serving others. When the mind is one-pointed, other internal and external activities are simply not a distraction.

The person with a one-pointed mind just carries on with the matters at hand, undisturbed, unaffected, and uninvolved with those other stimuli. It is important to note that this is meant in a positive way, not the negative way of not attending to other people or other internal priorities. The one-pointed mind is fully present in the moment and able to attend to people, thoughts, and emotions at will. The one-pointed mind is able to do the practices of concentration and meditation, leading one onward towards samadhi. This ability to focus attention is a primary skill that the student wants to develop for meditation and samadhi. 5. Niruddah/mastered: The nirruddah mind is highly mastered, controlled, regulated, restrained (Yoga Sutra 1.2). It is very difficult for one to capture the meaning of the Nirrudah state of mind by reading written descriptions. The real understanding of this state of mind comes only through practices of meditation and contemplation. When the word Nirrudah is translated as controlled, regulated, or restrained, it can easily be misunderstood to mean suppression of thoughts and emotions. To suppress thoughts and emotions is not healthy and this is not what is meant here. Rather, it has to do with that natural process when the mind is one-pointed and becomes progressively more still as meditation deepens. It is not that the thought patterns are not there, or are suppressed, but that attention moves inward, or beyond the stream of inner impressions. In that deep stillness, there is a mastery over the process of mind. It is that mastery that is meant by Nirrudah. In the second sutra of the Yoga Sutras, Yoga is defined as "Yogash Chitta Vritti Nirrudah," which is roughly translated as "Yoga is the control [Nirrudah] of the thought patterns of the mind field". Thus, this Nirrudah state of mind is the goal and definition of Yoga. It is the doorway by which we go beyond the mind.

What to do: Be aware of your state of mind: Be aware of your general state of mind. Which of the five is your typical state of mind in daily life? The single act of identifying your typical state of mind is very useful in moving that state of mind further along the path of Yoga meditation. If mind is kshipta or mudha: If your mind is mostly in the first two states (Kshipta or Mudha), how can you use the vast range of Yoga practices to bring the mind to the merely distracted (Vikshipta) state and then to one-pointedness (Ekagra)? How can you use other complementary practices or therapies to help in this process? If mind is vikshipta: If your mind is mostly in the distracted (Vikshipta) state, how can you work with your concentration practices to more fully bring the mind to the one-pointedness of the Ekagra mind? If mind is ekagra: If you are able to train your mind to be in the one-pointed (Ekagra) state, then how can you intensify your practices so as to attain glimpses of the mastery over mind called Nirrudah? Which of three qualities is most dominant? Three gunas or qualities: The mind has one of three qualities (three gunas) that predominate. These three qualities are related to the mind in general, as well as to specific thought patterns:

What to do: Cultivate sattvic mind: We want to cultivate the Sattvic or Illuminated state of mind, rather than a mind filled with Inertia or Negative Activity. The three gunas are said to be the building blocks of the universe, and at the same time are qualities of grosser levels of reality. For example, one might eat more Sattvic food as an aid to meditation, or create a Sattvic environment. Here, we are talking about cultivating Sattvic thought patterns. Notice which of the three is predominant: Here, we want to simply notice the state of mind in a common sense sort of way. This is very straightforward. The mind and its thoughts might be filled with a heaviness (tamas), filled with distracting activity (rajas), or it might be filled with illumination or spiritual lightness (sattvas).

Cultivate sattvic thoughts and emotions: In any case, we want to cultivate individual thoughts and emotions that are Sattvic in nature, that are spiritual, clear, or illumined. To do that, it is useful to label the Tamasic and Rajasic thoughts so that these can be transformed into Sattvic thoughts. It is not a matter of repressing the Tamasic or Rajasic thoughts, but of positively emphasizing the Sattvic.

It's not good or bad: When considering which of the Gunas are strongest in a given thought or thought process, it can seem as if Sattvas is "good" and that Tamas and Rajas are "bad". This is not the case. What is important is that balance of the Gunas and which one is dominant. In addition to the possible negative aspects, Rajas is also the positive impelling force to take actions, and Tamas is a stabilizing force. Both are useful. Allow sattvas to be dominant: For meditation, Sattvas is the Guna that the student wants to be dominant, allowing Rajas and Tamas to have little influence. Is this particular thought colored or not-colored Klishta or aklishta: Thought patterns are either Klishta or Aklishta.

See also the article on Klisha and Aklishta Vrittis, as well as Yoga Sutras, particularly sutras 1.5-1.11 and 2.1-2.9. A most important practice: To observe whether thoughts are Klishta or Aklishta is extremely useful. It is the foundation practice of observing your thought process. This is done when observing both individual thoughts and trains of thoughts. This can seem so simple a practice as to brush over it as being unimportant, but this is a big mistake. Observing whether thoughts are colored or not colored is useful both at meditation time, and during the activities of daily life. Klishta, or colored thought patterns:

Aklishta, or not-colored thought patterns:

What to do: Observe the rise and fall of thoughts: Simply observe the individual thought patterns that naturally flow in the stream of the mind. They rise and fall as a normal process. Then, simply observe whether a certain thought pattern is Colored or Not-Colored, Klishta or Aklishta.

Talk with yourself: The way to observe is to literally ask yourself with your inner voice, "Is this thought colored or not colored, klishta or aklishta?" Answers will come from within.

Verbalize the words: You will then want to train your mind by internally saying the word or label, such as "Colored," "Not-Colored," "Klishta" or "Aklishta". (This goes along with the process of observing whether the thought is Useful or Not Useful, which is described in a section below.) The process might go something like this:

With a little practice, the process comes very quickly, something like this:

Or:

Or:

Intentionally allow a thought to arise: Practice this by intentionally allowing a thought pattern to arise from within, and then observe and label it. Do this practice several times allowing different types of thought patterns to arise. With practice, this will be a very easy thing to do. Then, as a natural outcome of the observing and labeling process, it becomes much easier to become a neutral witness to that stream of thought patterns. Examine individual thoughts: When we can neutrally witness the entire stream of thoughts, it is then easier to examine individual thought patterns, so as to further weaken their grip (weakening the samskaras that drive karma). It is also easier to begin to move beyond the mind itself, towards the center of consciousness. Allow colored to become uncolored: We come to see that a most important aspect of yoga meditation has to do with allowing Colored or Klishta thoughts to naturally transition into Uncolored or Aklishta thoughts. The original thought remains, but gradually loses its coloring (mostly attraction and aversion), resulting in those previously troublesome thoughts becoming mere memories. This is a practical method of attaining the true meaning of non-attachment (vairagya). Which of five types is this particular thought? Then notice which of five types: Once you have observed whether a thought pattern is colored or not colored (klishta or aklishta), then the next step is to notice which of five types it is. You need not memorize the Sanskrit words, though that might come naturally as you practice this aspect of self-awareness. (Yoga Sutra 1.6)

Yoga deals with pramana/correct knowing: Yoga really deals with the first kind of thought, that of Pramana, or seeing correctly. In a sense, we could ignore the other four. However, it is useful to know about, and to observe the other four, so that we can intentionally focus on training the mind to see clearly. It is this correct knowledge that is the key to advancement on the spiritual journey.

What to do: Start with an individual thought: Observe an individual thought and simply notice which of these five types (above) most relates to that individual thought.

What we might notice: Here's some examples of what we might notice:

An example of type and coloring: Determining the type of thought (the five types above) is a next step, after labeling whether the thought is Colored or Not Colored. Together, we might then observe, for example,

Which of three ways do I know what is correct? Cultivate correct perception: In the previous section, five types of thought were presented. One of them is that of having correct knowledge or information, of seeing clearly (Pramana). This correct seeing is the one we want to cultivate. But how does one know what is true and what is not true, or false? Three ways to get correct knowing: Yoga describes three ways of having correct knowledge (Yoga Sutra 1.7). Simply noting these three ways does not automatically mean you know what is true, but it can be a good start. The three ways of having correct information are:

What to do: Be aware of correct perception: This is an ongoing process of observing the ways in which we draw conclusions about the day to day objects and activities around us, as well as about spiritual truths.

The goal of Yoga is to ultimately see Truth completely clearly. Thus, the process of identifying the means of knowing true from not true is very important.

Seek convergence of the three ways of knowing: As we move along the path, we come to see a convergence of direct experience, inference, and the testimony of others who have tread the path. When all three ways of knowing seem to agree on a given subject, we have a pretty good indication that we are going in the right direction. To look for the points of convergence of experience, inference, and teachings can be a very practical aid on the spiritual path. By which of five colorings is this thought influenced? Five kinds of colorings: These colorings or kleshas are of five kinds. The kleshas can be understood both in a very practical way that applies to our gross thinking process, and they can also be understood in very subtle ways. Here, we are mostly looking at the grosser ways of observing the kleshas. The depth comes in the practice of deeper meditation. See also the article on Klisha and Aklishta Vrittis, as well as Yoga Sutras, particularly sutras 1.5 and 2.3.

The five kleshas or colorings are as follows, and are further described in the text further below:

Reading the descriptions of the five colorings (kleshas) can sound philosophical rather than practice. As you read through them, pay particular attention to attraction (raga) and aversion (dvesha). You will quickly see how practical this process is as a part of your meditation, and life. Witness day-to-day thoughts: Remember, we are not talking here about any special kinds of thought. These are the typical, day to day thoughts, or memories that naturally arise in meditation. What we are talking about in this section is the way in which those typical thoughts are colored. It is easiest to start by witnessing the colorings of attraction and aversion. Gradually the other colorings will become obvious as well.

1) Avidya, spiritual forgetting, ignorance, veiling: Vidya is with knowledge: Vidya means knowledge, specifically the knowledge of Truth. It is not a mere mental knowledge, but the spiritual realization that is beyond the mind. When the "A" is put in front of Vidya (to make it Avidya), the "A" means without. Avidya is without knowledge: Thus, Avidya means without Truth or without knowledge. It is the first form of forgetting the spiritual Reality. It is not just a thought pattern in the conventional sense of a thought pattern. Rather, it is the very ground of losing touch with the Reality of being the ocean of Oneness, of pure Consciousness. See also Yoga Sutras 2.1-2.9, particularly sutra 2.5 on the four types of avidya or ignorance. Meaning of ignorance: Avidya is usually translated as ignorance, which is a good word, so long as we keep in mind the subtlety of the meaning. It is not a matter of gaining more knowledge, like going to school, and having this add up to receiving a degree. Rather, ignorance is something that is removed, like removing clouds that obstruct the view. Then, with the ignorance (or clouds) removed, we see knowledge or Vidya clearly. Even in English, this principle is in the word ignorance. Notice that the word contains the root of ignore, which is an ability that is not necessarily negative. The ability to ignore allows the ability to focus. Imagine that you are in a busy restaurant, and are having a conversation with your friend. To listen to your friend means both focusing on listening, while also ignoring the other conversations going on around you. However, in the path of Self-realization, we want to see past the veil of ignorance, to no longer ignore, and to see clearly.

Avidya is the ground for the other colorings: Avidya is like a fabric, like a screen on which a movie might then be projected. It is the ground in which comes the other four of the colorings described below. Avidya (ignorance) is somewhat like making a mistake, in which one thing is confused for another. Four major forms of this are:

Both large and small scales: As you reflect on these forms of Avidya, you will notice that they apply at both large scales and smaller scales, such as the impermanence of both the planet Earth and the object we hold in our hand. The same breadth applies to the others as well. Avidya gets us entangled in the first place: In relation to individual thought patterns, it is Avidya (spiritual forgetting) that allows us to get entangled in the thought in the first place. If in the moment the thought arises, there is also complete spiritual awareness (Vidya) of Truth, then there is simply no room for I-ness to get involved, nor attraction, nor aversion, nor fear. There would be only spiritual awareness along with a stream of impressions that had no power to draw attention into their sway. Witnessing this Avidya (spiritual forgetting) in relation to thoughts is the practice. 2) Asmita, associated with I-ness:Nature of I-ness: Asmita is the finest form of individuality. It is not I-am-ness, as when we say, "I am a man or woman," or "I am a person from this or that country". Rather, it is I-ness that has not taken on any of those identities. See also Yoga Sutras 2.1-2.9, particularly sutra 2.6 on the nature of I-ness or ego. See also the Two Egos section of Four Functions of Mind. Mistake of thinking it is about me: However, when we see I-ness or Asmita as a coloring, a klesha, we are seeing that a kind of mistake has been made. The mistake is that the thought pattern of the object is falsely associated with I-ness (Asmita), and thus we say that the thought pattern is a klishta thought pattern, or a klishta vritti. The image in the mind is not neutral: Imagine some thought that it is not colored by I-ness. Such an un-colored thought would have no ability to distract your mind during meditation, nor to control your actions. Actually, there are many such neutral thought patterns. For example, we encounter many people in daily life whom we may recognize, but have never met, and for whom their memory in our mind is neither colored with attraction nor aversion. It simply means that the image of those people is stored in the mind, but that it is neutral, not colored. Uncoloring your thoughts: Imagine how nice it would be if you could regulate this coloring process itself. Then, if there were an attraction or aversion, we could un-color it, internally, so as to be free from its control (or attenuate it). This is done as a part of the process of meditation. It not only has benefits in our relationship with the world, but also purifies the mind so as to experience deeper meditation. See also the article on Klisha and Aklishta Vrittis, as well as Yoga Sutras, particularly sutras 1.5-1.11 and 2.1-2.9 on uncoloring thoughts. I-ness is necessary for the others: In relation to individual thought patterns, the coloring of I-ness is necessary for attraction, aversion, and fear to have any power. Thus, the I-ness itself is seen as a coloring process of the thoughts. The practice is that of witnessing this Asmita (I-ness), and how it comes into relation with though patterns. 3) Raga, attraction or drawing to: Once there is the primary forgetting called Avidya, and the rising of individuality called Asmita, there is now the potential for attachment, or Raga.

Attachment is an obstacle, but not bad: Raga is not a moral issue; it is not "bad" that there is attachment. It seems to be built into the universe and the makeup of all living creatures, including humans. Degree of coloring: Where we get into trouble with attachment, is the degree of the coloring. If the coloring gets strong enough to control us, without restraint, we may call it addiction or neurosis, in a psychological sense. Gaining mastery: In spiritual practices, we want to gain mastery over the attachments. At meditation time, we want to be able to let go of the attachments, so that we might experience the Truth that is deeper, or on the other side from the attachments. Attachment is a natural habit of mind: However, in the process of witnessing, we want to be aware of the many ways in which the mind habitually becomes attached. If you see this as a natural action of the mind, it is much easier to accept, without feeling that something is wrong with your own mind. The habit of the mind to attach can actually become amusing, bringing a smile to the face, as you increasingly are free from the attachment. Witnessing is necessary for meditation: In relation to individual thoughts, attachment is one of the two colorings that is most easily seen, along with aversion. To witness attachments and aversions is a necessary skill to develop for meditation. The ability to let go of the train of thoughts is based on the solid foundation of seeing and labeling individual thoughts as being colored with attachment. 4) Dvesha, aversion or pushing away: Aversion is a form of attachment: Aversion is actually another form of attachment. It is what we are trying to mentally push away, but that pushing away is also a form of connection, just as much as attachment is a way of pulling towards us.

Aversion is a natural part of the mind: Dvesha actually seems to be a natural part of the universal process, as we build a precarious mental balance between the many attractions and the many aversions. Aversion is both surface and subtle: It is important to remember that aversion can be very subtle, and that this subtlety will be revealed with deeper meditation. However, it is also quite visible on the more surface level as well. It is here, on the surface that we can begin the process of witnessing our aversions. Aversion can be easier to notice than attachment: In relation to individual thought patterns, aversion is one of the two colorings that is most easily seen, along with attachment. Actually, aversion can be easier to notice than attachment, in that there is often an emotional response, such as anger, irritation, or anxiety. Such an emotional response may be mild or strong. Because of these kinds of responses, which animate through the sensations of the physical body, this aspect of witnessing can be very easily done right in the middle of daily life, along with meditation time. Attenuating the colorings: Notice the process of attenuating the colorings in the next section. To follow this attenuating process, it is first necessary to be aware of the colorings, such as aversion and attachment. Gradually, through the attenuating process, we truly can become a witness to the entire stream of the thinking process. This sets the stage for deeper meditation. 5) Abhinivesha, resistance to loss, fear: Once the balance has been attained between the many attractions and aversions, along with having the foundation I-ness and spiritual ignorance, there comes an innate desire to keep things just the way they are.

Fear of change: There is a resistance and fear that comes with the possibility of losing the current situation. It is like a fear of death, though it does not just mean death of the physical body. Often, this fear is not consciously experienced. It is common for a person new to meditation to say, "But I have no fear!" Then, after some time there arises a subtle fear, as one becomes more aware of the inner process. Fear is natural: This is definitely not a matter of trying to create fear in people. Rather, it is a natural part of the process of thinning out the thick blanket of colored thought patterns. There is a recognition of letting go of our unconsciously cherished attachments and aversions. When meditation is practiced gently and systematically, this fear is seen as less of an obstacle.

What to do: Allow streams of individual thoughts to flow: One of the best ways to get a good understanding of witnessing the kleshas (colorings) is to sit quietly and intentionally allow streams of individual thoughts to arise. This doesn't mean thinking or worrying. It literally is an experiment in which you intentionally let an image come. It is easiest to do with what seem to be insignificant impressions. For example, imagine a fruit, and notice what comes to mind. An apple may come to mind, and you simply note "Attraction" if you like it, or are drawn to it. It may not be a strong coloring, but maybe you notice there is some coloring. You may think of a pear, and note that there is an ever so slight "aversion" because you do not like pears. Experiment with colorings: Allow lots of such to images come. One of the things I have done often with people is to grab about 10-15 small stones in my hand, and ask a person to pick one they like. Then I ask them to pick one they are less drawn to (few people will say they "dislike" one of the stones). It is a very simple experiment that demonstrates the way in which attractions and aversions are born. It is easier at first to experiment with witnessing thoughts for which there is only slight coloring, only a small amount of attraction or aversion. You can easily run such experiments with many objects arising into the field of mind from the unconscious. You can also easily do this by observing the world around you. Notice the countless ways in which your attention is drawn to this or that object or person, but gently or strongly turns away from other objects or people. Though it is a bit harder to do, notice the countless objects you pass by everyday for which there is no response whatsoever. These are examples of neutral impressions in the mind field. Gradually witness stronger colorings: By observing in this way, it is easier to gradually witness stronger attractions and aversions in a similar way. When we can begin the process of witnessing the type of coloring, then we can start the process of attenuating the coloring, which is discussed in the next section. In which of four stages is this colored thought pattern? Systematically reduce the colorings: These colorings (kleshas) are either: 1) active, 2) cut off, 3) attenuated, or 4) dormant. We want to be able to observe and witness these stages so that we can systematically reduce the coloring. Then the thought patterns are no longer obstacles to deep meditation, and that is the goal. See also Yoga Sutra 2.4 on the four stages of coloring. Review: For clarity, let's quickly go over what has been covered so far, in relation to witnessing a thought:

It's not so complicated: Hopefully, when you read these few points above, the process of labeling and witnessing is now starting to seem not so complicated. It really is easy to see all of this in a moment, and the internal labeling takes only a few seconds. It really does get easier with practice. Four stages of coloring: Now, we want to know what to do about these colorings that are normally obstacles to meditation and spiritual realization, and which often cause trouble in our external lives; that is, in the world of other people, situations, and circumstances. The starting point is to observe what is the current state of the coloring: 1. Active, aroused (udaram): Is the thought pattern active on the surface of the mind, or playing itself out through physical actions (through the instruments of action, called karmendriyas, which include motion, grasping, and speaking)? These thought patterns and actions may be mild, extreme, or somewhere in between. However, in any case, they are active. 2. Distanced, separated, cut off (vicchinna): Is the thought pattern less active right now, due to there being some distance or separation. We experience this often when the object of our desire is not physically in our presence. The attraction or aversion, for example, is still there, but not in as active a form as if the object were right in front of us. It is as if we forgot about the object for the now. It is actually still colored, but just not active (but also not really attenuated). 3. Attenuated, weakened (tanu): Has the thought pattern not just been interrupted, but actually been weakened or attenuated? Sometimes we can think that a deep habit pattern has been attenuated, but it really has not been weakened. When we are not in the presence of the object of attachment or aversion, that separation can appear to be attenuation, when it actually is just not seen in the moment. This is one of the big traps of changing the habits or conditionings of the mind. First, it is true that we need to get some separation from the active stage to the distanced stage, but then it is essential to start to attenuate the power of the coloring of the thought pattern. 4. Dormant, latent, seed (prasupta): Is the thought pattern in a dormant or latent form, as if it were a seed that is not growing at the moment, but which could grow in the right circumstances? The thought pattern might be temporarily in a dormant state, such as when asleep, or when the mind is distracted elsewhere. However, when some other thought process comes, or some visual or auditory image comes in through the eyes and ears, the thought pattern is awakened again, with all of its coloring.

Where does all of this go? Through the process of Yoga meditation, the thought patterns are gradually weakened, then can mostly remain in a dormant state. Then, in deep meditation the "seed" of the dormant can eventually be burned, and a burned seed can no longer grow. Then, one is free from that previously colored thought pattern. Example: An example will help to understand the way these four stages work together. We'll use the physical example of four people, in relation to smoking cigarettes, because the example can be so clear. The principles apply not only to objects such as cigarettes, but also to people, opinions, concepts, beliefs, thoughts or emotions.

What to do: Notice the stage of individual thoughts: We want to observe our thinking process often, in a gentle, non-judging way, noticing the stage of the coloring of thought patterns. It can be great fun, not just hard work. The mind is quite amusing the way that it so easily and quickly goes here and there, both internally and through the senses, seeking out and reacting to the objects of desire. There are many thoughts traveling in the train of mind, and many are colored. This is how the mind works; it is not good or bad. By noticing the colored thought patterns, understanding their nature by labeling them, we can increasingly become a witness to the whole process, and in turn, become free from the coloring. Then, the spiritual insights can more easily come to the forefront of awareness in life and meditation.

Train the mind about coloring: An extremely important part of attenuating, or reducing the coloring of the colored thought pattern is to train the mind that this coloring is going to bring nothing but further trouble. It means training the mind that, "This is not useful!" (This is discussed in the next section). This simple training is the beginning of attenuating the coloring (The process starts with observing, but then moves on to attenuating). It is similar to training a small child; it all begins by labeling and saying what is useful and not useful. Note that this is not a moral judgment as to what is good or bad. It is more like saying whether it is more useful to go left or right when taking a journey. Often, we are stuck in a cycle: Often in life, we find that the colored thought patterns move between active and separated stages, and then back to active. They go in a cycle between these two. Either they are actively causing challenges, or we are able to get some distance from them, like taking a vacation. Break the cycle: However, it is possible that we may never really attenuate them when engaged in such a cycle, let alone get the colorings down into seed form, when we are stuck in this cycle. It is important to be aware of this possibility, so that we can intentionally pursue the process of weakening the strength of the coloring.

Meditation attenuates coloring: This is where meditation can be of tremendous value in getting free from these deep impressions. We sit quietly, focusing the mind, yet intentionally allow the cycling process to play out, right in front of our awareness. Gradually it weakens, so we can experience the deeper silence, where we can come in greater touch with the spiritual aspects of meditation. Will I train my mind as to what is useful and not useful? Are you willing to train your mind?: Recall that at the beginning of the paper, we spoke of negative thoughts as an example of labeling thoughts. We used the simple example of internally saying, "Negative" to label such a thought.

Now, the next piece of the process is to evaluate whether the thought is Useful or Not Useful. This, in turn leads to the question of whether we will, or will not cultivate this thought, and whether we will or will not allow it to turn into actions. We may ask, for example, "Should I do it, or not do it?" "Should I give this any energy, or let it go?" A simple sequence might be like this:

Or, like this:

Or, to be quiet for meditation:

Cultivate the higher function of mind: The evaluation of thoughts being Useful or Not Useful comes from using the function of mind called buddhi, which is the aspect of mind most important to cultivate. Most often, it is pretty obvious whether a thought is Useful or Not Useful. However, consciously noticing this is a very important part of training the mind.

Talk to yourself: Then, you literally say to your mind either "Useful" or "Not Useful". This is spoken internally, not aloud. It is somewhat the way one might train a small child. It is done very lovingly, but with a clear statement of the reality of being Useful or Not Useful. To say that a thought is Not Useful makes it easier to then let go of the thought without it turning into a long train of Not Useful thoughts. It is also easier for the thought to not turn into actions that are occurring only out of habit. Cultivate the useful thoughts: If a thought is Useful, then it is easier to cultivate that thought, and bring it into action in the external world if that is appropriate. In this way, more of the Useful thoughts are cultivated, while more of the Not Useful thoughts are dropped. This is an extremely useful part of the process of stabilizing and purifying the mind, which sets the stage for advanced meditation and samadhi. This labeling applies to all types of thoughts: To label thoughts as Useful or Not Useful applies to virtually all of the types of witnessing that are being described here in this paper. How does this relate to the Four Functions of Mind? All of the witnessing practices described here play out in the field of the Four Functions of Mind. The more the individual aspects are labeled and witnessed, the more one comes to see the elegant simplicity of the inner process of the four functions.

From where did the thought come?: In consciously working with witnessing the Four Functions of Mind, you can ask yourself, "From where did this thought, emotion, sensation, image, or impression arise?" It is not a question of life history or psychodynamics, but of logistics. Where was this thought pattern located a moment ago, just before it arose? You come to see that it arose from the place it was resting, the reservoir of the mind-field called chitta in Yoga science. Whatever thought arises, it is always true that it arose from chitta. So why should you ask yourself where the thought came from, if the answer is always the same? It is a part of self-training, of becoming a witness to the process. Further, it allows you to have some distance from the thought itself. It allow you to see clearly, instantly, in the moment, that, "This thought is not who I am! I am different from my thoughts! I am the one who is witness of all of these thought patterns!" How did this thought come to affect me?: Then, it allows you to be able to pose the question, the reflection, "How did I get caught up in this thought pattern? How did I get entangled in this, thinking that this is who I am? That this has something to do with me? Why is this thought pattern not neutral? Why is it not a mere memory?"

You come to see the coloring agent, the one who took this otherwise neutral thought pattern, this mere memory, and turn it into something more, into a false identity of "who I am". You come to see the effect of ahamkara, the ego. A case of mistaken identity: You see that a mistake has been made--the mistake of the ego thinking that this thought pattern has something to do with me. When that wisdom comes, it means that the function of mind called buddhi is now seeing clearly, and the manas, or mind is now much more free from those thought patterns, rather than automatically reacting out of habit or conditioned response. A very high practice: Witnessing the interplay of the Four Functions of Mind is a very high practice on the path of Self-Realization. Because there are only four processes to witness, there is also a simplicity to it. It is not easy to do initially, but there really is a simplicity to it. One hundred percent of the processes of the mind involve only these four functions. By becoming witness to these four processes, one is automatically moved in the direction of realizing the Self or Atman, since that is ultimately the highest stance from which witnessing occurs. How does this relate to the Levels of Consciousness? To understand the relation between witnessing and the levels of consciousness, you might want to also review these two papers: Latent level of consciousness: When the colored thought patterns (klishta vrittis) are in a latent, dormant form, they reside in the third level of consciousness (see below). This is the level called Prajna, which is also the Deep Sleep, Subconscious, or Causal level.

Subtle level of consciousness: When those thought patterns begin to stir, the thought patterns start to interact in the Taijasa level, which is also the Dreaming, Unconscious, or Subtle. The thought patterns have not actually gone anywhere, traveled anywhere. Rather, the state of consciousness has shifted; they have simply become active, though it is not seen consciously, in the waking state. Gross level of consciousness: When the thought patterns break through the threshold between conscious, and unconscious, they are experienced at the Vaishvanara level, which is also the Waking, Conscious, or Gross. Now, the thought patterns can begin to effect actions and speech, as well as thoughts. Obviously a person can be in the conscious state and not consciously aware of the thinking process that is driving the actions. This is how our unconscious process controls us, and this is part of the reason we want to become aware. Do not block the levels of consciousness: Sometimes, it is easy to think that if we can simply block these deeper levels, we can sit in the waking state and enjoy deep meditation. It may be peaceful to do this, but it will not bring deep meditation. The deep Silence, Self, Atman, or Absolute Reality is underneath, or beyond the other levels and the colored thought patterns. Therefore, it is essential to learn how to open the veil to the deeper layer.

Three parts to opening the veil: In opening the veil, there are three principles or aspects of practice that go together:

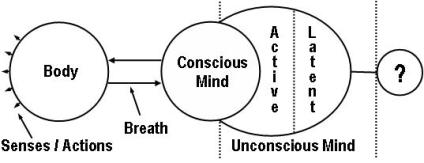

With these three abilities, one can then witness the field of consciousness, and begin the journey beyond. Where does this fit in with other yoga practices? Body, breath, and mind: It is most useful to work with the grosser aspects of body, breath, and mind. Then you are better able to do these witnessing practices. It does not mean that you cannot begin the labeling and witnessing practices immediately--that would not be true. However, the foundation practices are really quite beneficial. If the body is uncomfortable, the breath erratic, and the mind troubled, then these witnessing practices might end up worry sessions rather than peaceful, contemplative observations. See also the article Seven Skills to Cultivate for Meditation.

The witnessing practices set the stage for the deeper practices of meditation, wherein you consciously, intentionally, willfully allow your attention to go into the space beyond all of the processes of mind. Theoretically, one could go directly to that space, bypassing all of the other work, including with body, breath, and mind, including these witnessing practices. However, to directly go beyond all of this is extremely difficult and might not be the better approach for most seekers. Position of witnessing in practice: A simple way of graphically describing the relative position of these witnessing practices is like this:

To be able to witness your thinking process means first having the mind somewhat stable. The witnessing skill is then cultivated. This in turn leads to deep meditation. Witnessing in meditation Discriminating in meditation: Ultimately, the one stance from which all of these thoughts and aspects of mind can be witnessed is the Self, the Atman. In Yoga, the process is described as discriminating between Purusha and Prakriti (approximately, though crudely translated as consciousness and matter). See also the Witnessing Notes and Discrimination Notes on the Yoga Sutras.

Know yourself: By whichever philosophical model one follows, this process of labeling and witnessing thought processes and patterns is a profoundly useful practice on the path to Enlightenment. It is a major part of the perennial wisdom that suggests that you, "Know Yourself" to follow the spiritual journey. It is the journey from the mere self to the True Self. Witnessing is an essential skill: The ability to witness the individual thoughts and the whole stream of thoughts is one of the important skills in practicing meditation. In this way meditation can turn into the higher state of samadhi. It means that the mind is truly able to focus without being disturbed. Then, this focus (one-pointedness called ekagra) and the quality of being undisturbed by the thoughts (non-attachment, or vairagya) can allow a natural piercing of the layers of consciousness, and expansion to That which is beyond. Patience and practice: To do this process of labeling and witnessing requires patience and practice. Like most things, it can look difficult at first, though it truly is an easy thing to do.

-------

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||